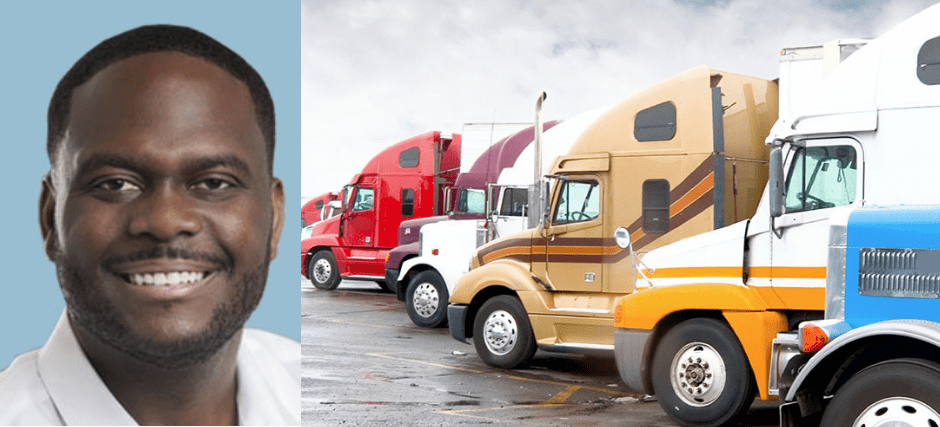

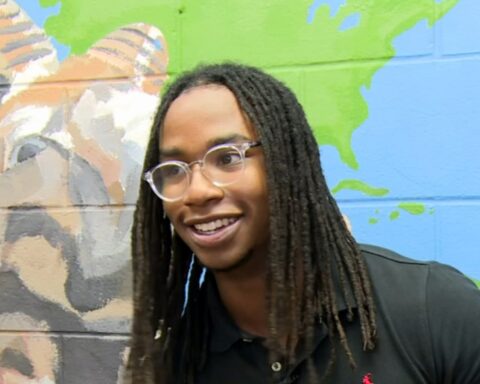

This Entrepreneur Went From Being Homeless To Running a Million Dollar Logistics Company

Raised in a military family, Amari Ruff literally saw the world. At 16, his father left Amari’s mom to raise their three children, forcing Amari to balance a heavy work schedule with the demands of High School.

During this unsettling period, Amari’s family moved between relatives and homeless shelters. At one point, Amari had to commute over four hours a day, via public education, to maintain continuity at his High School.

Accepted to college, Amari was unable to cover the costs, forcing him to take a job as a cable company technician. He quickly moved up the ranks and began negotiating significant enterprise contracts.

Realizing he had a knack for establishing relationships and crafting mutually beneficial business deals, Amari began a telecommunications company in 2010, with $300 and a 1990 Ford Ranger. He built the business to almost 200 trucks and five locations across the U.S. However, Amari realized that a larger opportunity existed for a tech company to connect minority, women and veteran led businesses with large corporations.

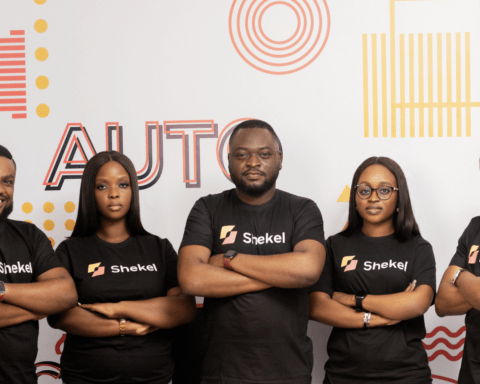

In 2015, Amari launched Sudu. Never one to think small, Amari landed Wal-Mart as his first enterprise customer. He subsequently cut deals with P&G, Delta Airlines, Georgia Pacific and UPS. Sudu now has over 300,000 trucking companies within its network and is generating millions in revenue.

Greathouse: Amari, thanks for taking the time to share your entrepreneurial journey with me and my readers. You’ve demonstrated a level of focus and perseverance that every entrepreneur can learn from. Let’s start by providing a brief overview of Sudu’s value proposition.

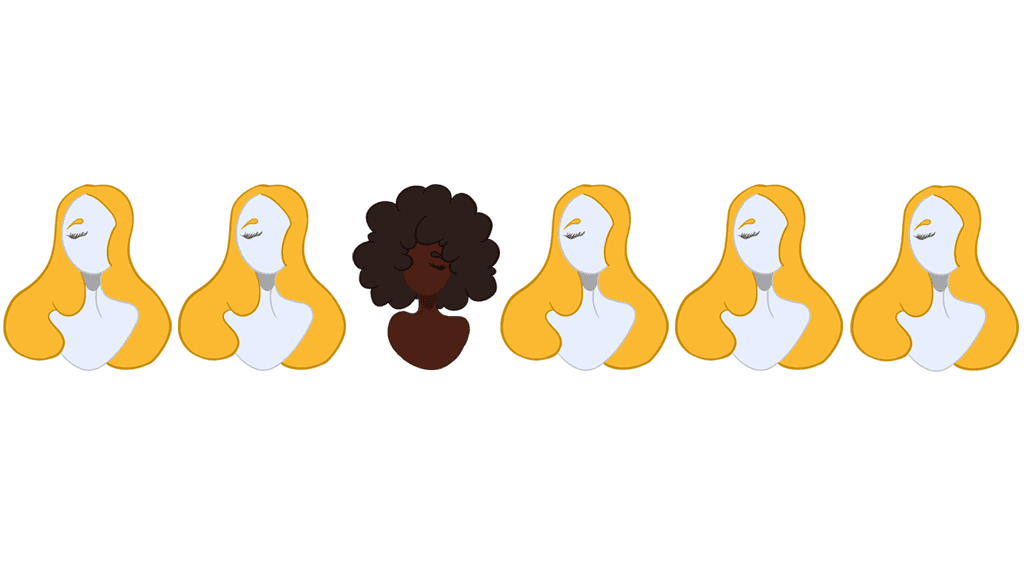

Amari Ruff: My pleasure John. First off, Sudu is a marketplace that leverages technology to connect small and medium sized trucking companies, which make up 90% or the trucking market, to corporations that ship goods. When we first entered the market, our initial focus was on minority, women and veteran owned trucking companies. We work with all trucking companies, but we identified these groups as the majority of the underserved market.

In the trucking industry today, in order for small and medium sized trucking companies to gain access to quality freight opportunities, they have to go through a freight broker. This is due to their capacity, access to capital, infrastructure and scalability. Also, large corporations don’t have the bandwidth to work with small companies. So, we developed a platform where that leverages the size of the network and allows for shippers and truckers to transact seamlessly.

We, of course, have competitors. But we differentiate in the way we communicate with our trucker network. Our competitors rely on a mobile app for sole communication with their truckers. Sudu doesn’t require our truckers to change their current behavior. Our platform allows truckers to choose their most comfortable means of communication. This has helped us when it comes to platform adoption.

Greathouse: What motivated you to start the company – startup origin stories often provide insight into a venture’s mission and culture.

Ruff: Agreed, that’s certainly the case with Sudu. I choose the name because it means “speed and tempo” in Chinese. I’ve always loved and respected the Chinese culture and it spoke really well to the speed and efficiency we provide the industry from a tech perspective.

After exiting my previous company, where I owned over 200 trucks, I had a vision to start a traditional asset-based trucking company. The goal was to build a company that was heavily focused on company culture and create an environment that owner operator truckers would want to be a part of.

I connected with a local trucking association here in Atlanta to gain more knowledge around the industry and discovered how fragmented and inefficient the industry was. Ninety percent of all trucking companies had 6 or less trucks within their fleet and diverse truckers (minority, women and veteran owned) made up a large portion of that underserved market.

In order for the ninety percent to gain access (to) quality freight opportunities, they would need to have at least 100 trucks, access to capital, quality infrastructure and be scalable. So, they go through freight brokers, which are glorified call centers. Their only goal is to maximize margins off of every transaction, (offering) no value add back to the trucker or shipper.

Looking at this $700B industry problem, I knew there had to be a better way to drive speed and efficiency. The plan was to harness diverse trucking companies and layer technology on top. This would help corporations with Supplier Diversity initiatives meet their goals, provide better pricing, due to leveraging tech and not human capital and also help an underserved market be in a better position to make additional revenue without having to do anything different. With this biz model, I felt that it would be a no brainer for both sides of our marketplace to choose Sudu.

Greathouse: You had an turbulent childhood, moving around a lot. As the product of a military family, I can relate. I’ve always felt that having to constantly make new friends provided me with social skills that I later leverage as an entrepreneur.

In what ways has your nomadic childhood impacted your entrepreneurial journey? To be more specific, you lived in Korea, Alaska… did your exposure to atypical cultures help you to close deals and expand your company?

Ruff: Absolutely! (laughing) When you move to a different city or country every few years, you have to learn how to make friends fast, otherwise you will not have any. You have to learn how to adapt quickly and make the best out of any situation.

I absolutely learned those skills from being a product of a military family. Today I leverage those same skills to excel in biz dev and sales and (I’ve become) extremely strong in dealing with multiple personalities.

I’m proud to say that I’m an extremely open-minded individual because of all my experiences in a military family.

Greathouse: In addition to moving often, you also shouldered the responsibility of financially helping your mother and sisters, while you were still young. In what ways have you used your experiences as a young breadwinner to successfully build your multi-million-dollar company?

Ruff: When your back is against the wall, us as individuals have two choices, we could give in to the circumstances, or do what it takes to work our way out. And I choose to do what I could for my mother and sisters.

I really just followed in the footsteps of my mother. She went from being a military wife and home mom, to working 2 full-time jobs to support 3 kids on her own, in a city where she had no family and no one to lean on. I was at the age where I could understand the hard work and sacrifice and it just rubbed off on me.

Surviving those trials and tribulations gave me the mindset that we as human beings can handle any situation placed in front of us as long as we know it’s temporary. And that has been my mindset ever since. I believe that’s the type of mindset you need to be an entrepreneur.

Greathouse: Agreed – though it seldom feels that way at the time, every stage in life is temporary. What kept you motivated to take that leap into entrepreneurship… especially given that you grew up in a household without business role models?

Ruff: I knew that I wanted more out of life than just the minimum. My mother always instilled in us that we weren’t regular and to never just do the minimum. Always give it everything you got and always strive to be the best that you can be. So, when I look to start a biz venture, my thinking is always BIG! I can’t remember who said it but, “if your dreams don’t scare you, you’re not dreaming BIG enough.” I really believe that!

Greathouse: Amen. Comfortable dreams are good for sleeping, but not for building a business. Speaking of acting “big,” I admire how you were fearless, especially in your early days. What gave you the courage to reach out and secure major clients such as Wal-Mart and UPS when you had no prior experience?

Ruff: I had no prior logistics or transportation experience, but I did have experience in doing business at the enterprise level. So, I had a good understanding of the enterprise procurement process and how they buy. Plus, I really believe in what we’re doing here at Sudu.

I knew we could bring additional value to corporations and I just needed a chance to bring awareness to who we were. I just needed that one shot! This also goes back to my beliefs from growing up where I didn’t build this company to just do the minimum.

Greathouse: Yea, doing the minimum usually results in minimal results. (laughs)

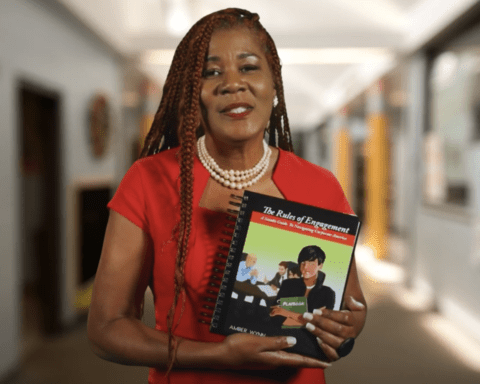

A lot of companies talk about the importance of diversity. However, you and your team have based your business model on ensuring the success of minority, women and veteran led companies. Do you have any suggestions as to what companies with well-intentioned, but ineffectual diversity initiatives can do to impact the tech community’s diversity imbalance?

Ruff: My suggestion would be to build better relationships with inner city High Schools and HBCU’s (Historically black colleges and universities).

Get more involved, do popup events to educate diverse students on what a career within their corporation would look like and what they look for in employees. I’m sure the schools would be open to it.

Greathouse: Makes sense. I’m currently working with the Black Studies department at UC Santa Barbara to see what I can do to facilitate the recruitment of minority students by Santa Barbara tech companies. Many companies want to diversify their workforces, but they struggle with basic outreach.

Thanks again Amari, you’re an inspiration. Continued best of luck to you and the entire Sudu team.

Source: Forbes