62 Black Women Who Are Writing Hits for TV and Hollywood

For The Hollywood Reporter’s largest shoot ever, members of Black Women Who Brunch, a networking group co-founded by Lena Waithe, gather to discuss how the industry can better understand black women in Hollywood: “We have to be exceptional.”

In 2014, Nkechi Okoro Carroll was an executive story editor on Bones when she met an up-and-coming scribe named Lena Waithe at a WGA Committee of Black Writers event. The two hit it off, so much so that Okoro Carroll got the future Emmy winner — whose major credit at the time was writing for the Nickelodeon series How to Rock — hired as a staff writer on her Fox procedural, making Waithe the second black woman in the room. “Aren’t you worried she’s going to take your job?” a fellow writer on staff asked Okoro Carroll.

“You should be worried she’ll take your job,” retorted Okoro Carroll, now showrunning The CW’s All American. What the duo felt was not competition but kinship: “We often felt like unicorns,” Okoro Carroll says. “When someone asked me to recommend mid-level female writers [of color] for a job, I was appalled to realize I didn’t know many names.”

Together with Erika L. Johnson, then writing for BET’s Being Mary Jane, the women decided to create a network of black female TV writers themselves. Twelve assembled for the March 2014 inaugural meeting of what came to be known as Black Women Who Brunch (BWB); today, the membership nears 80. “This group is the proof” against and antidote to “people saying, ‘We can’t find any black female writers,'” says Johnson, now a co-executive producer on NBC’s upcoming The Village.

BWB holds potlucks at Okoro Carroll’s house every few months (usually about 30 members are available at one time) to toast triumphs and troubleshoot challenges. “It’s not just a community we’re building, but a resource,” says Waithe. “We really are able to recommend eight or nine black women for certain jobs.”

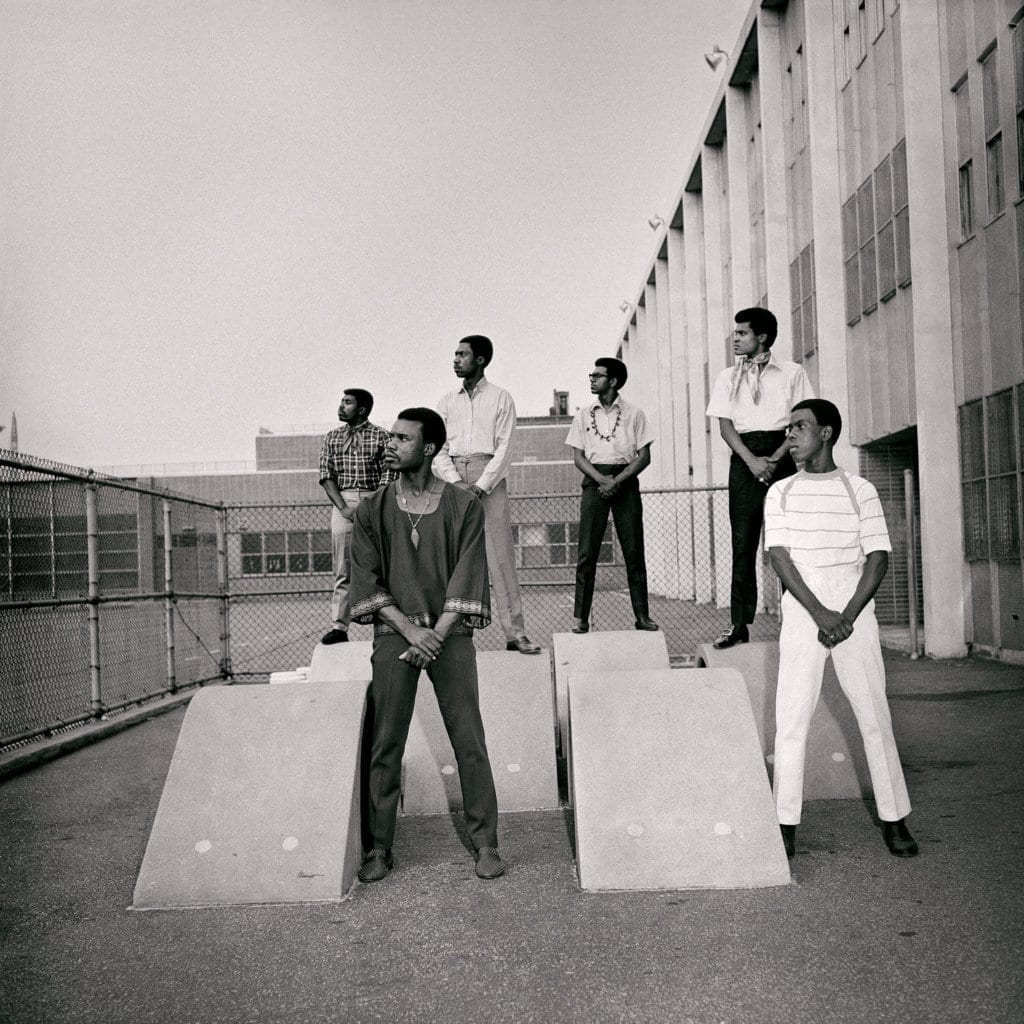

In August, BWB took its first off-site trip — a weekend getaway to Palm Springs. And in November, 62 members gathered for THR‘s biggest photo shoot ever, where they revealed what they wish their colleagues knew about being a black woman in the business.

THE BARRIERS IN THE PIPELINE

Ubah Mohamed, story editor, DC’s Legends of Tomorrow (The CW) It all stems from lack of information and access. As a child, I was fascinated by film and television but never dreamed of becoming a screenwriter. I didn’t know it was a real job. Growing up with immigrant parents in New York City, it was expected that I’d work in medicine or law. Children who lack access can’t imagine thriving in Hollywood because they don’t know those jobs exist, or how to get them.

Morenike Balogun Koch, producer, Jupiter’s Legacy (Netflix) Assistants of color are less likely to be looped in on or recommended for writer’s assistant openings because they are less likely to be asked to lunch or invited to social gatherings by their non-minority peers. You have to do the asking. There’s a weird social isolation going on. You’re just not thought of at times.

Felischa Marye, story editor, 13 Reasons Why (Netflix) People of color, who often don’t have the generational wealth or financial support system to attend film schools or work almost for free for years as an intern or assistant, are at a disadvantage. They are not in the pipeline.

Talicia Raggs, supervising producer, NCIS: New Orleans (CBS) Writer’s assistant is the best-known way to get your foot in the door to becoming a writer, but there’s only one position per show and it’s therefore the hardest to get.

Britt Matt, executive story editor, A.P. Bio (NBC) Before anyone even reads your material, you’re often already placed in a box or categorized based on your race and gender. Some showrunners won’t read you unless they’re looking for a writer that fits your demographic.

Pilar Golden, story editor, God Friended Me (CBS) In most rooms, there is only one of “us,” either male or female. When there is only one slot, you, along with every writer of color at every agency or unsigned, are vying for that.

Chantelle M. Wells, co-producer, Jane the Virgin (The CW) Writers coming out of the diversity programs are hit the hardest because the studio covers their pay for the first 20 weeks. After that, if the show decides to pick up their option for the rest of the season, their pay comes out of the show’s budget, as it does for every writer. Some shows won’t pick up those options and just bring in a new diversity hire they don’t have to pay for, under the guise of giving more people more opportunities. And what they’ve actually done is cut that writer at the knees because the next job they get, they’ll have to repeat staff writer because they’ve only had 20 weeks on a show.

Erica L. Anderson, supervising producer, 911 (Fox) Many women, including myself, have done staff writer multiple times.

Mercedes Valle, staff writer, Elena of Avalor (Disney Junior) I know at least two women of color who were staff writers five times.

Tash Gray, co-producer, Snowfall (FX) A writer on a “black show” who moves to a “non-black show” often has their level questioned, as if their experience is less valuable.

Jewel McPherson, executive story editor, Star (Fox) The numbers attest: Black showrunners represent only 5.1 percent of the pool. Nonblack showrunners, agents and studios enjoy the public praise they get for supporting lower-level diversity programs. However, they fail to promote capable writers of color to upper-level positions.

Thembi L. Banks, executive story editor, untitled Hilde Lysiak series (Apple) Being trusted to run your own show is one of the hardest battles. I see women who’ve worked in the business for over a decade struggle to get that position. I was about to take a pilot out for development and asked for a list of black women showrunners. The list seemed to be almost nonexistent.

Ester Lou Weithers, story editor, Star (Fox) Overqualified co-EPs of color, who should be on showrunner lists that agents send out and networks pull from, simply aren’t given the chance because “they’ve never done it before.”

Maisha Closson, co-EP, Claws (TNT) and How to Get Away With Murder (ABC) Any level is tough because a lot of EPs have the mentality that if they hire one person of color, they’ve hired enough people of color. But you walk into that room and there are five white guys. There’s no cap on them.

***

THE TOKEN IN THE ROOM?

Angela Harvey, supervising producer, Station 19 (ABC) The first season I was in a writers room, I was the only woman and the only POC. I would jokingly preface my pitches with, “Well, speaking for all the female and non-white persons of the world …,” hoping that a spoonful of humor would help the medicine go down. When you’re the only one in the room with a specific understanding of a story, there’s no one to kick ideas around with. It’s just you in the hot seat with 10 pairs of eyes boring into you. In some rooms, folks are genuinely trying to understand. In others — watch out.

Adrienne Carter, supervising producer, Family Reunion (Netflix) When I was writing on the third season of NBC’s Las Vegas, my partner and I were the only people of color. My first day on the job, the showrunner said there were too many characters on the show, and we needed to get rid of one. The consensus was to kill of Marsha Thomason’s character, and the guys got more and more excited as they decided she should die in a fiery explosion. I was horrified and said, “You can’t kill the only black woman on the show.” That had never occurred to them.

Franki Butler, story editor, upcoming Netflix series Having other POC in the room takes the burden of being The Minority Perspective off of my shoulders. I’ve been in rooms with upper-level POC writers, and that was incredibly important. As a staff writer, the one thing you absolutely never want to be is the person who stops the flow of the room, and there’s a fear that saying, “Um, this feels real effing offensive,” can do that. But when there’s someone on a higher level who can back your play, it turns into an actual discussion.

Erika Green Swafford, consulting producer, New Amsterdam (NBC) Sometimes it takes more than a couple of people to redirect the course of a character or a story. You can be dismissed if you are the lone voice. You need backup.

LaTonya Croff, story editor, Raven’s Home (Disney Channel) When there is more than one of anything in the room, it’s easier for a note to break through. Otherwise you have to be that one person passionately fighting and risk being labeled “difficult” or “not a good fit.” And someone labeled “difficult” does not return for season two.

Margaret Rose Lester, staff writer, Manifest (NBC) The pressure to represent the “black” voice can be frustrating and isolating because the idea of blackness people are looking for often aligns with stereotypes. When I can’t fulfill the story to support that stereotype, I feel as though I’ve failed in my contributions to the writing team.

Wendy Calhoun, consulting producer, Station 19 (ABC) I was the only woman in the Justified room during its first two seasons, so you can imagine how refreshing it was when I was pitching story on Nashville, which had a majority female writing staff. It meant I could spend more time pitching nuance and fresh takes, and less time explaining why I’m pitching the idea in the first place. That deep character dive happened in a different way on Empire season one, which was not a gender-balanced room but had more working black writers than I’d seen outside of a WGA event. We dissected black American music, stories and characters from every angle in that room.

Robinson Being the only one makes it difficult to pitch something you know is a killer joke or story that has a ton of specificity and you know your friends and family would die to see, but because you’re the only black person, you have to explain why it’s good or funny. And by the time you have, it’s a dead pitch. Sometimes just having one other black person or person of color helps because if I pitch something specific to black people, there’s someone there for it to land on. And it doesn’t matter that the white people don’t get it. if we’re making prestige cable television or a standout network comedy, you should be dying to include those types of moments that you, as a non-black writer, could never pitch.

Shari B. Ellis, animation production manager, Rainbow Rangers (Nickelodeon) On shows with predominantly black staffs, I’ve spent far less time explaining or second-guessing myself and my value, freeing me to concentrate on serving the needs of the production to the best of my ability.

Abby Ajayi, co-producer, Four Weddings and a Funeral (Hulu) On How to Get Away With Murder, there were seven women in the room and six were women of color. It didn’t fall on one person to be the voice of all women or all black people. Having multiple women from diverse ethnic backgrounds broadened the conversation, which in turn led to richer, deeper characters. It’s also inspiring to see the women higher up the ladder prove that there is a path.

LaToya Morgan, co-executive producer, Into the Badlands (AMC) The times when I was with another black writer were fantastic. The person I worked with was more experienced than I was, so I stepped up my game to match hers. I got the peer-to-peer mentorship that I’d always hoped I’d get from a showrunner but never did.

Nina Gloster, staff writer, Star (Fox) Having an ally in the room creates a much more safe space for creativity.

Matt No one wants to be known as “the race/gender police,” especially in a comedy room. When you have at least one ally (the more the better, for diverse points of view), you get to share that responsibility so you’re not “the one.” You also have someone to vent to, which makes things easier on your therapist.

Calaya Michelle Stallworth, staff writer, Daybreak (Netflix) Our showrunner, Aron Coleite, pulled together a diverse team: Nine people in the office. Seven in the room. Two African-American, two queer, five women (three writers), two Jewish people, three white men, five writers over 40. I was so proud of that each day. We were from all over the country and had diverse life experiences. I got to show up to work as a writer who happens to be black and a woman, and was never put into a position where I had to hold my tongue about minority characters. To add: While I was a staff writer neophyte, I was expected to talk and contribute.

Akilah Green, writer, A Legendary Christmas With John and Chrissy (NBC) What’s at least as important as the number of women and people of color in the room is that the people in charge believe not only in diversity but also in inclusion, in being allies and amplifying underrepresented voices. When you have women and people of color in the room but don’t actually empower them to speak up and don’t listen to them when they do, you end up with Kendall Jenner’s Pepsi commercial.

Shernold Edwards, co-executive producer, Anne With an E (Netflix); consulting producer, The Red Line (CBS) The difference lies with the showrunner. Anne With an E is based on Anne of Green Gables and is set in the 19th century. The first season is beautiful. It’s also very white. That was the first thing creator Moira Walley-Beckett brought up during my meeting. I told her I wasn’t interested in tokenism; turns out she wasn’t, either. I was part of the creation of the first black character ever to appear in the world of Anne, out of a series of 19 or so books. I got to name him and give him my parents’ Trinidadian heritage. He appeared in nine out of 10 episodes and had a thorough arc. So not tokenism — more like a step toward the healing of cultural erasure — because there have been black folks in Canada since about 1751, but it takes a creator who gives a shit enough to look past the source material and put that onscreen.

I WISH HOLLYWOOD UNDERSTOOD …

Jenina Kibuka, story editor, P-Valley (Starz) That we aren’t a monolithic group. We’re multidimensional and would like to be treated as such.

Wells That we work twice as hard (getting half as much) in order to defend ourselves against an assumption of mediocrity.

Marye That people assume that you got in through a diversity program, and if you did, it means you’re no good — that you only got your job because you’re black and no one’s hiring straight white males anymore, when statistics continuously contradict that notion.

Croff That most of the time, our road to the table was longer and harder than our counterparts’. So when we make it, know that it was earned. Nothing was given.

Stallworth That for decades black women creatives were told no and pushed aside. Some were forced to take other work, so you have black women screenwriters masquerading as lawyers because no one took them seriously. And now Hollywood is like, “There aren’t any black women who want to write sci-fi or edit films or do sound.”

Lena Waithe, creator/EP, The Chi (Showtime) That being a black woman in the industry is a gift and a curse: a gift because we’re in high demand right now, a curse because we’re also being commodified.

Edwards That this “angry black woman” stereotype really burns my ass. I’m a black woman, but I’m also Canadian. Stereotype that.

Keli Goff, story editor, Black Lightning (The CW) That it can be exhausting knowing that whatever you do, your successes or failures reflect on an entire group of people. I recently received a note: “Not many black women are up for opportunities like this, so it’s important for all of us that you give it your all.”

Kimberly Ann Harrison, co-EP, Star (Fox) That we can write for anyone, not just for black women.

Rasheda S. Crockett, staff writer, Adam Ruins Everything (truTV) That we have to be experts at cultural specifics that pertain to us, while being proficient at cultural specifics that don’t.

Matt How heavy our workload is: In addition to being a good writer, pitching jokes, being good in the room, etc., we also have to deal with speaking up when marginalized people are portrayed in a negative or stereotypical light.

Njeri Brown, co-producer, Dear White People (Netflix) That we’re not some hardened rebel force that can hold the weight of the world on our shoulders because we have a historical legacy of being strong. Sure, I’m a formidable black woman and I know quite a few like me in this business. But we are also soft and vulnerable, and the cost of being strong is sometimes having to take a Klonopin and do some breathing exercises, because we’re human. Just like you.

Marquita J. Robinson, co-producer, GLOW (Netflix) That we have such little room for error. We have to be exceptional. Those writers who always move up despite being “just OK”? None of them are black women. If a white male staff writer is bad, it’ll never keep those in power from hiring another white guy. I’ve heard people say that they “tried” to hire diverse, but the black writer they hired didn’t work out, so they never hired a black person again. Incredible.

THE BENEFITS OF BWB

Rochée Jeffrey, story editor, SMILF (Showtime); executive story editor, Step Up: High Water (YouTube Premium) Lena Waithe helped to put my name in front of Frankie Shaw for the writers room of SMILF season two.

Cynthia Adarkwa, staff writer, In the Vault (Complex Networks) Trying to traverse this unique career can at times be such a shitstorm. With these women, I’m able to air frustrations and talk strategy in a safe and judgment-free zone. I’ve bothered Erika Johnson quite a few times about career moves (sorry girl, but also thank you so much). It’s been priceless and keeps me going on the hardest days.

Kibuka Many of its members were responsible for helping to facilitate much of my incremental progress toward finally becoming a TV staff writer, such as guiding me in my management/agency search, helping with targeted prep for showrunner meetings and, most important, being an empathetic body of solace and strength when navigating the highs and lows of the creative process.

Stacey Evans Morgan, consulting producer, Family Time (Bounce TV) Iron sharpens iron, and when we come together to break bread, it’s comforting to know that there is a fellow sister scribe who has your back. The job information shared is also amazing, as one member may have the inside scoop on a staffing opportunity, and the ability to put in a good word with a showrunner on your behalf.

Resheida Brady, executive story editor, Good Trouble (Freeform) I was a writer’s assistant when I found out I was pregnant. I had my daughter and was unable to continue being an assistant. Three months later, I was unemployed when I was randomly called to interview for a writer’s assistant position at Being Mary Jane season four with [showrunner and BWB member] Erica Shelton Kodish. I got the job and was promoted to staff writer in a month. It turns out Erica had read my pilot and wanted to staff me all along. She had a 9-month-old, while I had a 3-month-old. She not only gave me my big break, but she also taught me a lot about being a working mother. She made sure I pumped on schedule and that I had enough milk stored up before she decided if we would work late. It was my big break as a writer, but an even bigger break working for her — a fellow black working mom.

Erica Shelton Kodish, showrunner, Being Mary Jane (BET), currently under a CBS TV overall development deal The support is paramount. When you’re out in the trenches, it can be very isolating. It’s extremely beneficial to know there is a group who keenly understands what you’re going through, who’s gone through it themselves and has helpful insights on how to navigate the politics.

Amani Walker, creator, Rebel (BET) The women in BWB are absolutely amazing at sharing job opportunities, especially during staffing season. They may have a leg up on a writing opportunity that might not be widely known and graciously share that information with the group.

Golden In our Facebook group, women are consistently uploading information and job opportunities. No lie, we’re each other’s agents.

Weithers Cue DJ Khaled’s “The Keys”! When you walk into that brunch, you are stepping into a wealth of knowledge, experience and encouragement. There are so many unwritten rules in the writers room that you need someone to help you navigate the landmines, especially when you get an offensive note or are the only woman or POC in the room. The same goes on the business side — these women can tell you when your agents are leaving opportunities on the table; it empowers you to know what has been done before and gives you the agency to fight for yourself.

Erika Harrison, producer, How to Get Away With Murder (ABC) I do some of my best writing after a BWB brunch. Creative juices flow like a mug.

Gray I have both comedy and drama credits as a direct result of BWB. When I decided to venture into drama, several women encouraged me, read my drama sample and passed my work on to their showrunners.

Morgan I’ve recommended people for jobs, introduced them to agents and representatives, and emotionally and financially supported their projects. I mentor several writers within the group, and my mentor is also part of the group. I always try to use whatever connections I make to help elevate all of us.

Marye After we went to Palm Springs this summer, a development executive saw our group shot that I posted on social media and reached out to me to find black female creators for new shows.

MICROAGGRESSION HORROR STORIES

Raamla Mohamed, co-executive producer, Little Fires Everywhere (Hulu) On set a PA directed me to background holding. A couple of times I was mistaken as a stand-in for Kerry Washington and also was asked if I was the script supervisor while I was sitting in a chair marked “writer.”

Erika L. Johnson, co-executive producer, The Village (NBC) “I met with a [white male] showrunner and we got along well and riffed off of each other. Toward the end, he looked at me almost in disbelief and said, “You’re really smart.”

Waithe I was in a writers room and Oprah’s Legends Ball had aired on TV. It inspired me and my mother. The next day, these white writers were like, “What the fuck was that?” I wanted to punch them. Just because something wasn’t about you doesn’t mean it’s not relevant.

Angela Nissel, co-EP, The Last O.G. (TBS) When people use their one black friend to explain why your point of view is wrong.

Jalysa Conway, story editor, Grey’s Anatomy (ABC) It’s very annoying when someone from the dominant race believes they know more about the “minority” experience and wants to enlighten the world about our struggles. We need allies, not self-described saviors.

Valle I wear a Stars Wars Rebel Alliance necklace most of the time and I can’t tell you how many guys have asked me if I know what the insignia stands for or where it’s from.

Ali Kinney, story editor, Single Parents (ABC) I’ve heard quite a few Caucasian colleagues say phrases like, “I don’t see color.” But being a person of color is a different experience. To deny that is not realistic and can actually be hurtful.

Carter My white boss, who fancied himself “down,” told me that my experience wasn’t valid because I wasn’t “really black.” As if being black and [Yale] educated cannot exist together.

Harvey Often when I try to add a layer to a story tinged with racism or misogyny, the reaction from the room is reluctance to turn a show into an “issues” show or make things too “political.” The moments I’m pitching are based on real-life experiences that happen to real people, not “very special episodes.”

Lisa Muse Bryant, supervising producer, Black-ish (ABC) Being told I’m too sensitive when I point out classic gags and jokes that are rooted in stereotypes.

Syreeta Singleton, staff writer, Central Park (Apple) Being in comedy rooms, there’s the question of whether or not you are being too sensitive when someone suggests that because you’re a black girl, you must be wearing a weave, or that black people have a harder time swimming than others. Where’s the line between playful teasing, creating a comfortable space, and being racist? All of people’s stereotypes and long-held beliefs — about black women, specifically — seem to rear their ugly heads in the form of “jokes.” I stood up once to get something and another writer suggested I was going to start twerking.

Lorna Clarke Osunsanmi, story editor, All American (The CW) When I have pointed out instances of institutional racism or scenarios where POC have been disproportionately impacted, I am called a racist.

Anonymous Once a showrunner went around the table asking each writer the name of their nanny growing up. I was the only person of color and come from a working-class immigrant family. The intention may not have been to make me the other, but that was the outcome.

Gray On a previous show, I said I’d read that black women are the most educated group in America. My white male counterpart, vigorously questioning this, grabbed his phone to search Google to prove me wrong. When the writers assistant, also a white male, supported my statement, the debate was over. Being female and black, I am constantly questioned or ignored unless I assert myself.

McPherson A person once said they were tired of trying to understand what was taboo to say about people of color. It was too much to keep up with.

Golden I have heard on a number of occasions people getting upset because “their” spot was taken. What a privilege to believe something is automatically yours with no regard for competition.

Kibuka I once had a [non-black] colleague who only used spirited, black vernacular when speaking with me.

Shalisha Francis, supervising producer, Seven Seconds (Netflix) The tendency for some non-POC [people of color] men to be less receptive when a woman disagrees or offers a counterpoint. I thought it would never be acknowledged till Glen Mazzara spoke at a WGA talk about the first time he realized he tensed up more when he received criticism from the women on his staff.

PLEASE STOP …

Banks Hiring women or black people solely because there is a woman or black character on your show. Our perspectives are broad and our narrative scope reaches beyond our gender and race.

Taii K. Austin, producer, House of Lies (Showtime) Requiring black writers also to be performers. I hope Lena Waithe and Issa Rae keep doing it for decades. But some of us want to stay behind the camera.

Nissel Being afraid to talk about race. And please stop calling us “angry” when we’re simply passionate. We’re nerds; we love TV!

JaNeika James, producer, Empire (Fox) Taking “no” for an answer when you can’t find a person of color.

Balogun Koch Telling me to “wait my turn” to develop my own ideas, despite there being interest in doing so, when my white male peers weren’t told that at all. I know. I’ve asked them.

Closson Asking me about Kwanzaa.

Robinson Asking me if I cut my hair. Natural hair shrinks. Write that on your arm and never ask me again.

***

PLEASE START …

Balogun Koch Asking us to lunch or drinks. Executives, showrunners and peers ask other writers. Include us; get to know us.

Wells Asking writers of color for recommendations. I make no secret about BWB and the talented women who populate this group, yet I can think of only one time when I was asked to recommend someone.

Marye Demanding from agents to read people of color specifically. And don’t stop when they send just one or two.

Morgan Asking agencies about new talent. That means not just sending out the usual-suspect seasoned writers with robust résumés.

JaSheika James, producer, Empire (Fox) Looking at how many black women executives networks and studios don’t have, and then hiring them. And if they have one or two … hire more.

Valle Hiring black writers even when there aren’t black characters in the main cast.

Austin Considering our creative range. I’d kill for the opportunity to adapt something like Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s [U.K. comedy] Crashing or to write a super-broad feature for Will Ferrell, but that’s not usually the sort of project a black woman is called in for.

Click the image below to see a larger version.

1 Talicia Raggs (drama – Verve, Sheree Guitar) 2 Zoanne Clack 3 Rochée Jeffrey (UTA, Rain, Frankfurt Kurnit) 4 Erika Green Swafford (drama – WME, Sheree Guitar, Hansen Jacobson) 5Ester Lou Weithers (drama – Paradigm, Circle of Confusion) 6 Erica L. Anderson (drama – Gersh) 7 Maisha Closson (drama – WME, The Cartel) 8 Erika Harrison (drama – UTA) 9 Nina Gloster (drama – CAA, Rain) 10 JaNeika James (drama – ICM, Industry, Hansen Jacobson) 11 Calaya Michelle Stallworth (CAA, Writ Large) 12 Brusta Brown (drama – The Cartel, Ziffren Brittenham) 13 Resheida Brady (drama – CAA, Rain) 14 Franki Butler (drama – Abrams, Echo Lake) 15 Ticona S. Joy (drama – CAA, Good Fear) 16 Pilar Golden (APA, Meridian) 17 Angela Harvey (drama – APA) 18 Chantelle M. Wells (drama – UTA, Industry) 19 Lisa McQuillan (comedy – UTA) 20 Lisa Muse Bryant (comedy, drama – Rothman Brecher, Sheree Guitar, Lichter Grossman) 21 Felischa Marye (comedy, drama – UTA, MetaMorphic) 22 Taii K. Austin (comedy – Hansen Jacobson) 23 Amani Walker 24 Raamla Mohamed (UTA, Ziffren Brittenham) 25 Morenike Balogun Koch (ICM) 26 Akilah Green (comedy – Scenario) 27LaTonya Croff (comedy – Sheree Guitar, Lichter Grossman) 28 LaToya Morgan (drama – CAA, Eclipse Law) 29 Erica Shelton Kodish (drama – CAA, Industry, Hansen Jacobson) 30Wendy Calhoun (drama – UTA, Brillstein) 31 Shernold Edwards (drama – UTA, Del Shaw) 32Shari B. Ellis (comedy, animation – Bohemia Group) 33 Jalysa Conway (drama – Gersh, Underground) 34 Lorna Clarke Osunsanmi (drama – Verve, Niad) 35 Thembi L. Banks (comedy, drama – UTA, Rain) 36 Njeri Brown (WME, Media Talent Group) 37 Rasheda S. Crockett (comedy – WME, Seven Summits) 38 Jewel McPherson (drama – CAA, Rain, Ivie McNeill) 39 JaSheika James (drama – ICM, Industry, Hansen Jacobson) 40 Marquita J. Robinson (comedy – CAA, Del Shaw) 41 Britt Matt (comedy – UTA) 42 Niya Palmer (comedy, drama – Smart) 43 Margaret Rose Lester (drama – UTA, Marathon) 44 Mercedes Valle (animation, dramedy, drama – The Arlook Group) 45 Adrienne Carter (comedy – Gersh) 46Ubah Mohamed (drama – Gersh, Kaplan Perrone) 47 Tash Gray (comedy, drama – Kaplan-Stahler, MetaMorphic, Ziffren Brittenham) 48 Syreeta Singleton (comedy – UTA) 49 Cynthia Adarkwa (drama, dramedy – Brillstein) 50 Angela Nissel (comedy – Kaplan-Stahler) 51 Diarra Kilpatrick 52 Ali Kinney (comedy – CAA, LBI) 53 Shalisha Francis (drama – CAA) 54 Keli Goff (drama – APA, Manage-Ment) 55 Abby Ajayi (drama – Gersh, the U.K.’s 42, Del Shaw) 56Stacey Evans Morgan (comedy – Tash Moseley) 57 Jenina Kibuka (drama – CAA, The Cartel, Ziffren Brittenham) 58 Nkechi Okoro Carroll 59 Erika L. Johnson (drama – Hansen Jacobson) 60 Lena Waithe (WME, The Mission) 61 Kimberly Ann Harrison (drama – WME) 62 Safura Fadavi

Source: Hollywood Reporter