Two sisters opened a Bed & Breakfast in Detroit

Working with a family member even on small projects can be challenging. But imagine trying to renovate a house, decorate it and open it as a bed and breakfast. That kind of a partnership can’t work if you have sibling rivalry.

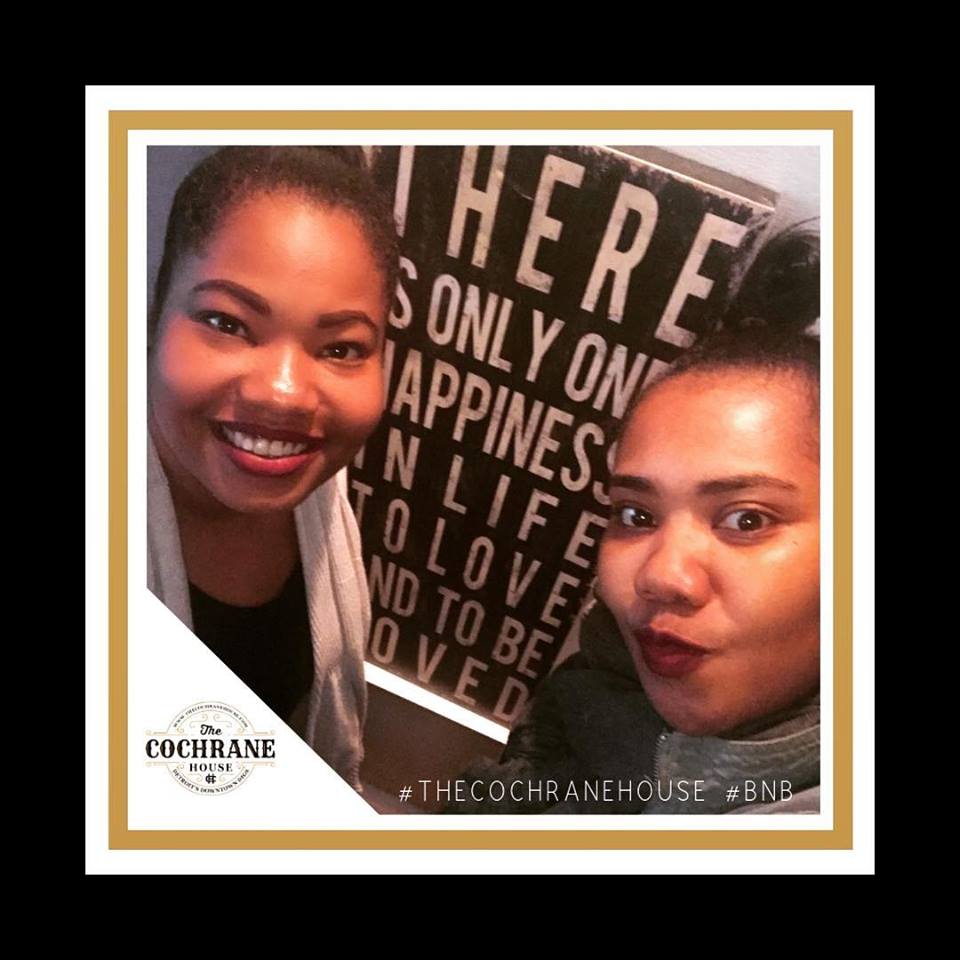

Sisters Roderica and Francina James are an example of how two siblings can work together, start their own business and support one another throughout the process. They are the owners of the Cochrane House Luxury Inn in Detroit, a new bed-and-breakfast hotel that opened in May.

These born-and-raised Detroiters aren’t hospitality experts. They don’t have a design background. In fact, they’ve never taken on a project this big before. But their mutual respect, admiration for each other’s strengths and balance of each other’s weaknesses made The Cochrane a possibility and, after six months of guests, a true success.

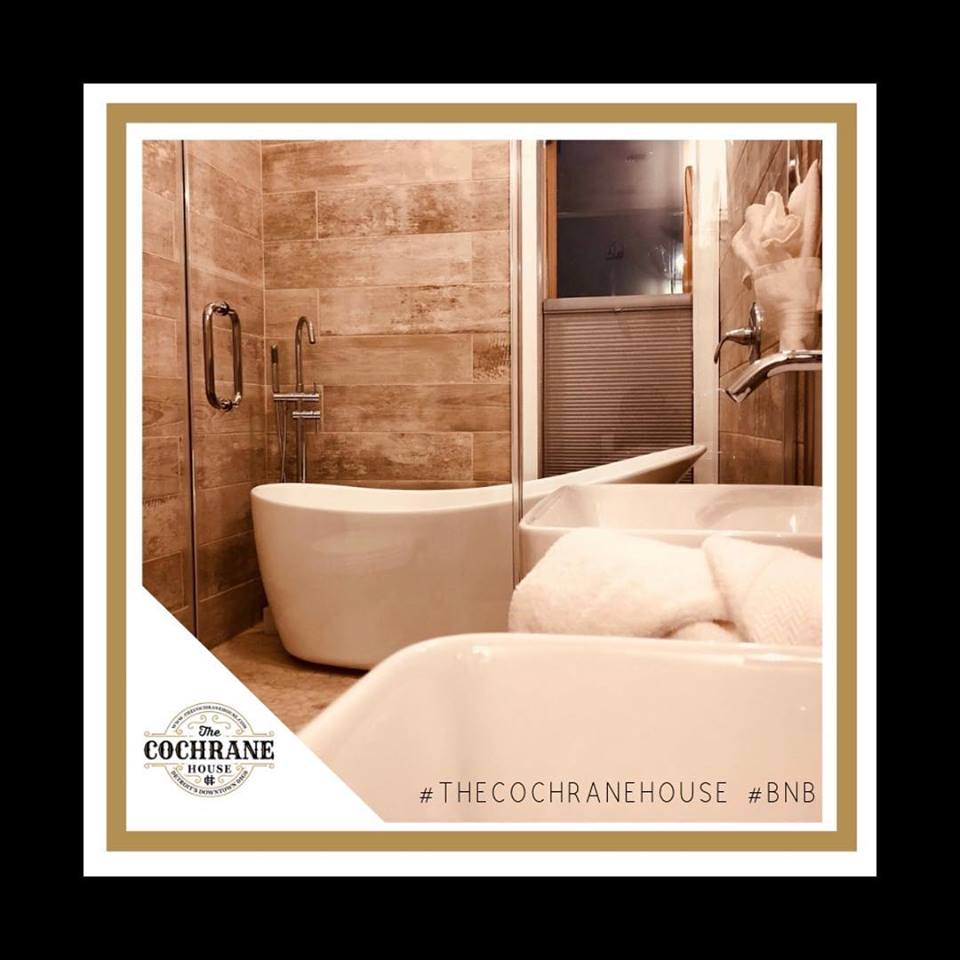

The bed and breakfast has three guest rooms, a homemade cooked breakfast delivered to the room, hand poured house made soap, and specialized Cochrane House candles.

The Cochrane House also has customized packages for private parties and events.The Bed & Breakfast is walking distance from all three major sport arenas and theater district in Detroit.

“We want people to come in and relax, play music, a board game or have a glass or wine. Our whole goal is for our guests to be in an atmosphere where their mind, body, and soul is relaxed.

We want our guests to have the best experience possible. When you walk into the doors you can feel the family atmosphere.” says Founder and Owner of The Cochrane House Roderica James.

Life experience

These sisters have a wide range of experience and skills that they bring to The Cochrane House. Co-Owner Francina James is a graduate of Martin Luther King Jr., senior high school. She graduated from the University of Michigan and has held various position in the educational field. She is also a graduate from Thomas M. Cooley Law School and is currently a licensed attorney.

Roderica started a nail business in high school and continued throughout college. James graduated from Eastern Michigan University and began working in education. She worked at Pepper Elementary School in Oak Park, where she started as a teacher and later on became the Student Intervention Specialist.

At 23, she began working with her mother at EduTech Tutoring Company. Noted as one of the largest tutoring companies in Detroit, she served as executive director. James then expanded the business to Atlanta, Georgia and Jackson, Mississippi where she became Southern Regional Director.

“My sister and I are 13 months apart. We went to the same elementary, middle and high schools. She went to Michigan while I went to Eastern. So we’ve been close our entire lives,” Roderica said. “Of course, we have our disagreements. But because we know each other so well, we know how to listen to each other’s ideas.”

Francina agrees. “Roderica is the whimsical one, the one with the best ideas and entrepreneurial spirit. I’d say I’m the realistic one, the logical one. Whenever she has an idea, I give her suggestions on how to bring it down to Earth a bit so we can get it done.”

A dream fulfilled

Roderica started renovations on The Cochrane House in 2013. The home was erected in 1870 for Dr. John Terry, a Detroit eye doctor who decided to build his home in the Brush Park neighborhood. He lived in this mansion only for one year, before Lyman Cochrane purchased it. In 1871, Lyman Cochrane not only occupied this beautiful home, but also was elected to represent Detroit in the Michigan State Senate.

He served for two years and was later appointed Judge of the Superior Court of Detroit in 1873. He served in that position until February of 1879, the time of his death. He took pride in scholarship and was presumed to have one of the most extensive and valuable private libraries in the city of Detroit.

With family support, persistence and patience, Roderica’s dream has come true. Just on the heels of turning 40, James is proud to have a business in the city where she grew up.

“I feel blessed and honored. My position gives other women an opportunity to see someone at my age dedicated to something for so long finally come to fruition. It’s not easy, but my journey shows other young people, if you stay dedicated and focused, you are able to do it,” says Roderica.

Source: CORP

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9823749/Julian_abele.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9823755/resolver_20_3_.0.jpeg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9823759/resolver_20_4_.0.jpeg)

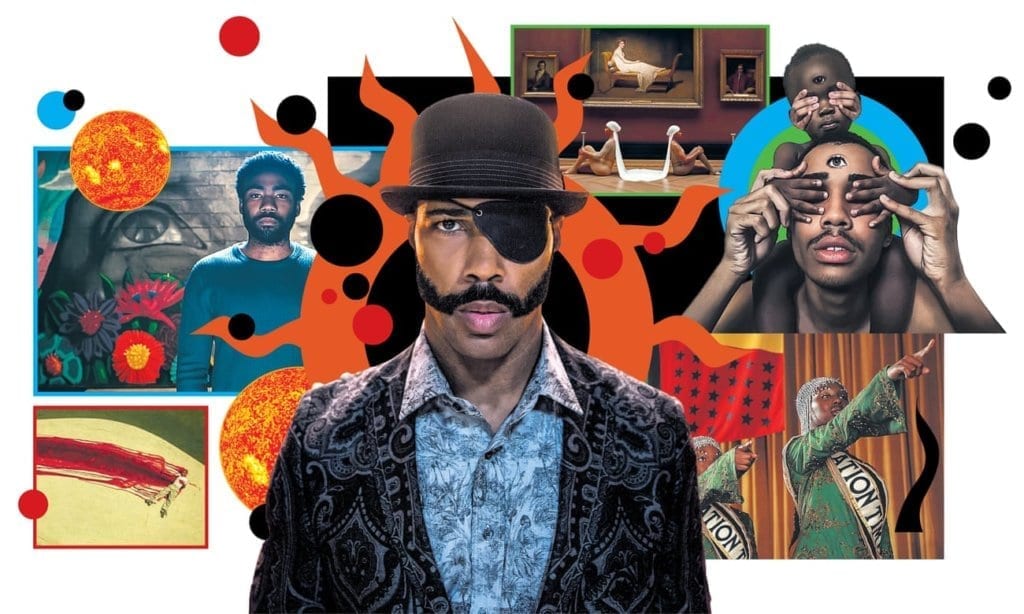

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9823825/resolver_20_2_.0.jpeg)