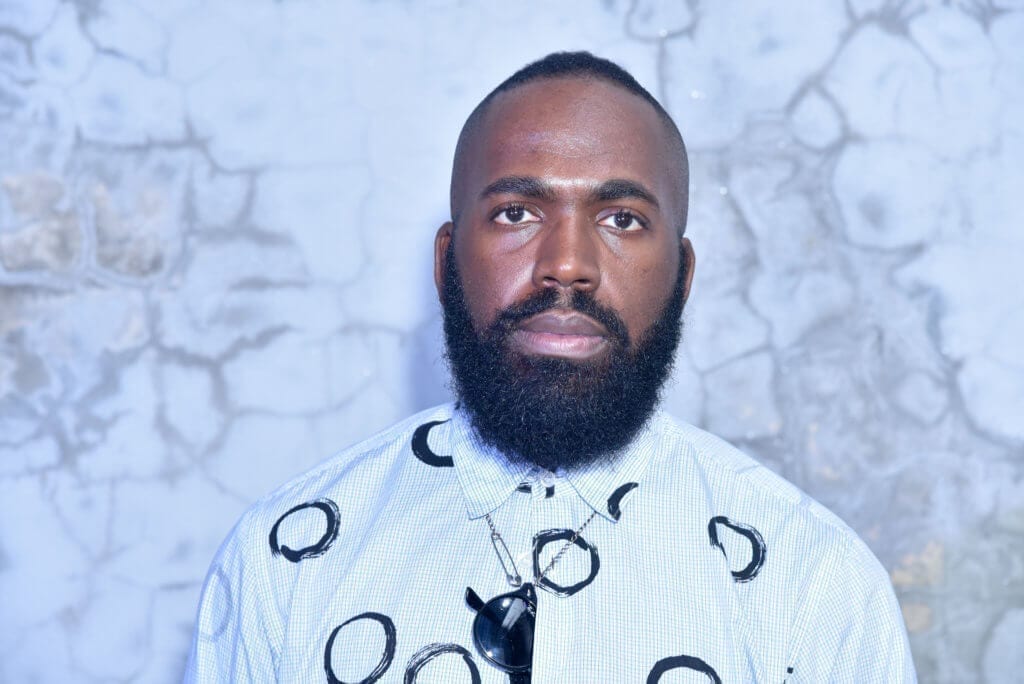

Why Aren’t There More Black Fashion Designers?

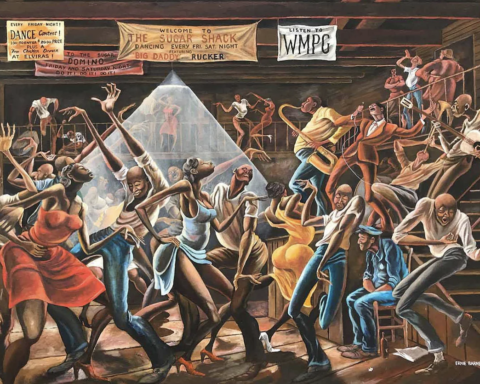

Within a fashion industry that touts itself as celebratory of difference, diversity, and inclusion, Black design talent consistently remains, at best, marginalised and all too often plagued by systemic employment discrimination.

Let me be clear: the established, mainstream fashion design community does not have a diversity problem, it has a “Black people problem.”

Within the majority of luxury, contemporary-level and mass-market design studios, talented Black designers are seldom equitably afforded opportunities to attain senior designer, design director, creative director or vice president of design titles.

More often than not, they are blacklisted by influential recruiters and hiring managers, resulting in little to no prospects for stable employment or market rate salaries.

Fed up with watching this most blatant form of discrimination thrive while the broader industry capitalises on Black celebrity associations and the recent uptick in Black casting, I decided to do something.

Over the holidays, I began conceiving what would become a social media campaign; the goal was to ask and answer my own questions, in hopes of developing a plan for how the fashion design community could move toward fairer hiring practices.

On Wednesday, January 3rd #BreakSilenceBreakCeilings went live.

A few days thereafter, H&M depicted a young Black boy in a hoodie reading “coolest monkey in the jungle”, confirming how recklessly fashion brands with little to no Black leadership utilise images of Black people. (The Swedish retailer has appointed a diversity leader since the incident.)

In fashion, timing is everything, and the time has come for the industry to remedy the systemic marginalisation of Black design talent.

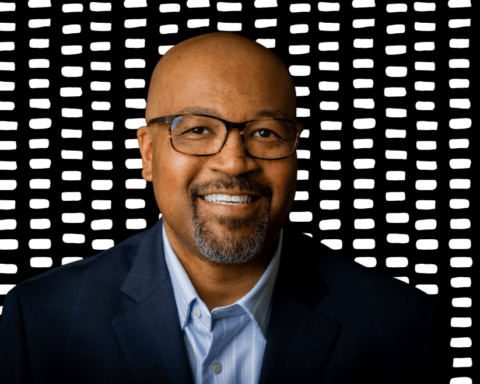

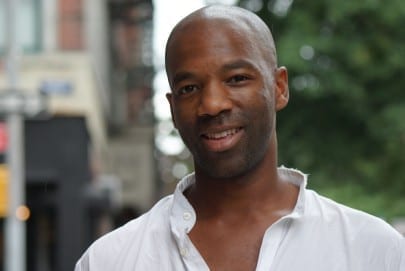

My path to working in fashion was non-traditional. Back in 1997, when I was struggling to find my footing and secure loans to attend New York University, I was offered a role as a designer at Michael Kors where I’d been interning for two seasons.

As my prospects for financing school waned, I enthusiastically accepted the role and threw myself into the challenge of mastering a new craft.

I was not formally trained in apparel design (save for a few courses I had taken at Pratt), but having grown up the son of two architects, I was very comfortable with technical drafting. My sketching ability became my value to the team, as I designed hardware details, show-specific accessories and communicated styling directives via illustration across categories.

Over the course of the next decade, as I landed roles within the studios of Isaac Mizrahi, Oscar de la Renta, Ralph Lauren, Gap Inc., J. Mendel and An Original Penguin, I grew strong in my abilities to lead fittings, appraise and select fabrics, and build colour stories as well as nurture talent, predict market trends and build valuable vendor relationships.

But within the professional environments in which I worked, I rarely encountered another Black face. Wherever I worked, I was consistently the highest titled Black team member. I was also consistently making considerably less money than my non-Black counterparts.

By the early aughts, headhunters were still reaching out, but I noticed that they rarely seemed to passionately advocate for me in the manner that many of my non-Black peers enjoyed.

Read the full article at Business of Fashion