Although the nail industry is dominated largely by Vietnamese women, there is an emerging interest in the billion-dollar market coming from a group of people that some would least expect: Black men.

Data from the UCLA Labor Center shows that only 2% of nail salon workers are Black, an even smaller fraction of that percentage are Black men. However, the market is shifting as more men enter into fields that fall outside society’s gendered norm.

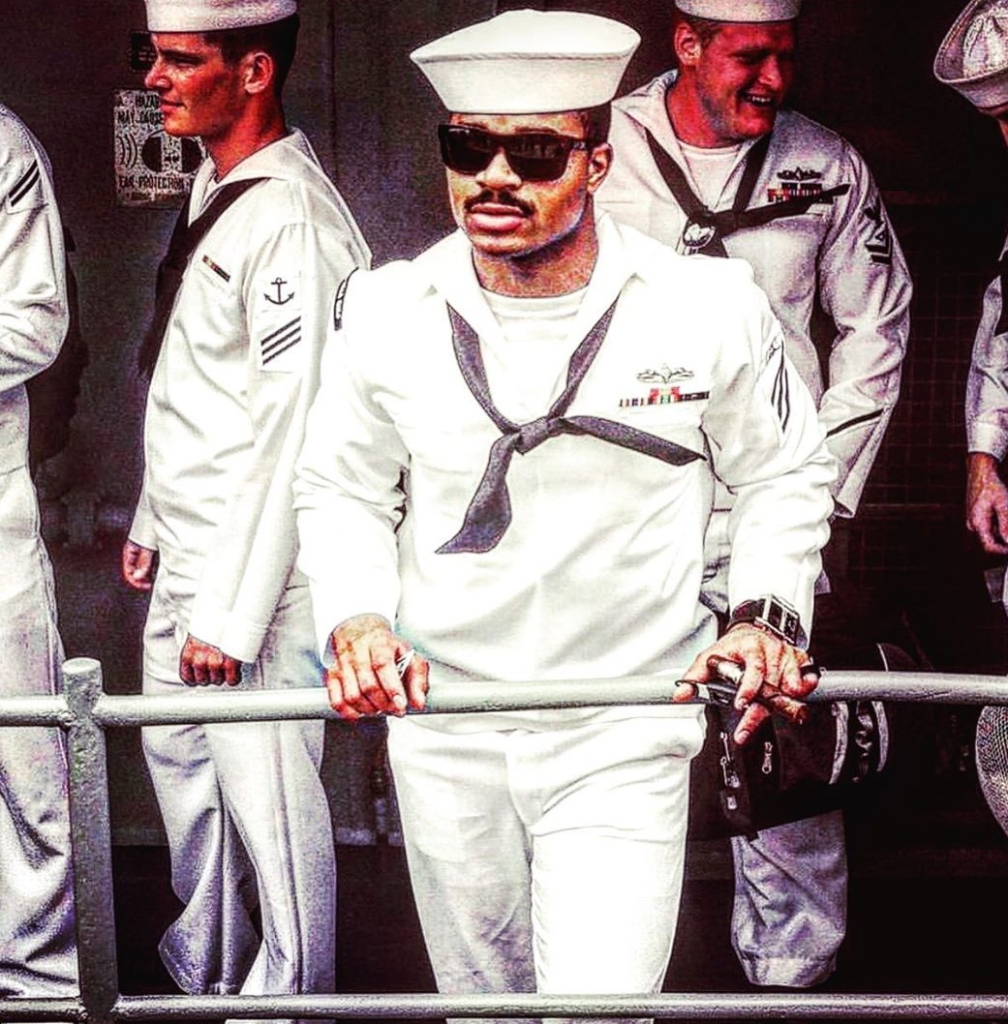

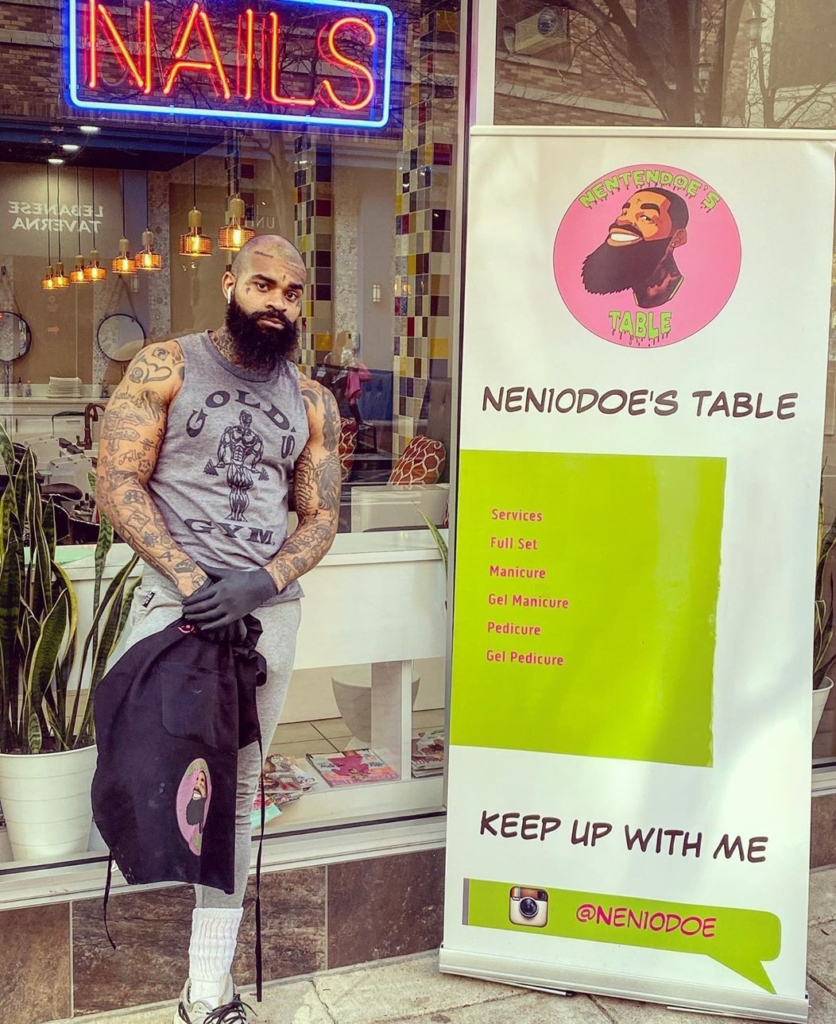

Darnell Atkins, who goes by Nen10doe on social media, is a 29-year-old nail technician from Washington, D.C. He began his journey in the nail industry after getting kicked out of the U.S. Navy because of his past addiction to synthetic marijuana.

When he returned home from serving his country, it was hard for him to find a job. In need of money, he looked to the streets to make ends meet.

“I resorted back to a couple of hustles,” Atkins said. “But in the midst of me resorting back, I always found myself in front of a Black-owned nail salon. All the hustlers would gravitate towards this area because that is where all the pretty girls were.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/CCcMMziB3NG/

Atkins went into the nail shop to inquire about a manicure and pedicure but was surprised when he found out it would cost him $70. Once he realized how much money nail technicians made, he decided that very day to get training.

“I was hungry, and I was motivated to find a way out,” Atkins said. ‘I didn’t have anything else, so I dumped all of my money into learning how to do nails.”

A few days later he began his training. But he did so in secret. He would walk to the shop with his hood over his head, hoping that no one would recognize him. Atkins said he was afraid that people would “think he was gay for wanting to do nails.”

“I didn’t want anybody to see. I was kind of ashamed,” he said.

Atkins hadn’t seen any Black men in his neighborhood do nails. There is a heavy stigma that comes with it and most decide it’s not worth society questioning their masculinity.

Ogundele Cain, a recent graduate from Virginia State University, agrees with Atkins. The 25-year-old has aspirations to break into the nail industry but doesn’t know any Black male nail technicians.

“I never saw a lot of Black men doing nails, and I definitely never saw a lot of Black straight men doing nails either,” Cain said.

Cain was supposed to enroll in cosmetology school this semester, but the coronavirus halted his plans.“I’ve always been vocal about breaking out of the patriarchy and away from society’s viewpoint of what masculinity should be,” he said. “The goal is to break the mold.”

There is a long history of society denying Black men the privilege of creating their own standards of what it means to be masculine. There are strict parameters around their masculinity that other races do not have the burden to abide by. Now, more than ever, Black people are taking their identities into their own hands.

Ekatarina Bender from Silver Spring brings her daughter to get her nails done by Atkins. He was the first Black male nail technician she had ever met. In her opinion, he is the best technician she has ever had. “At this point, it is super important for me to invest in him,” Bender said.

She likes that Atkins is not afraid to be different, and she said it’s important to her to be a loyal client and support his movement of defying gender norms.

Atkins’ goal is to inspire other Black men to pursue things they are interested in without feeling ashamed.“I want to do good work and be noticed for that, rather than the guy that just started doing nails and people are like, ‘that’s not normal,’” Atkins said. “Let’s make a big impact out of not being normal.”

Source:WUSA9

Subscribe and Follow SHOPPE BLACK on Facebook, Instagram &Twitter

Get your SHOPPE BLACK Apparel!