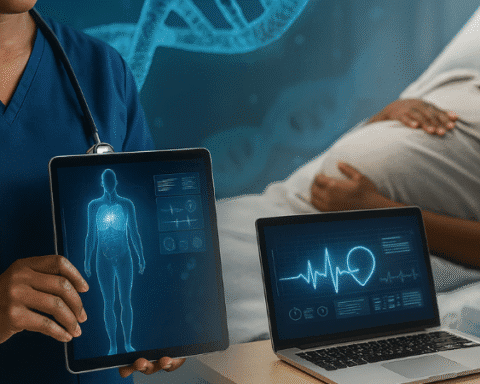

Health technology adoption has accelerated over the past decade, yet population health metrics have improved only incrementally.

Tools for diagnostics, care navigation, monitoring, and analytics proliferate across markets. Yet improvements in cost, access, and population health outcomes remain uneven and slow to materialize.

This divergence reflects how innovation is designed, financed, and deployed within fragmented systems.

Health innovation scales quickly because it is built to move through existing structures. Health outcomes improve slowly because they depend on changes those structures are not designed to support.

Innovation Is Optimized for Deployability

Most health innovation enters the system as a discrete, modular product. Point solutions integrate into limited slices of care delivery, such as scheduling, documentation, triage, billing, or monitoring.

This design is rational. Modular tools are easier to fund, procure, and deploy. They fit existing workflows without requiring broad institutional change.

Deployability is rewarded at every stage. Early funding prioritizes adoption signals. Procurement favors tools that minimize disruption.

Pilots are structured to demonstrate short-term operational efficiency rather than long-term outcome improvement.

As a result, innovation spreads rapidly at the edges of care while leaving core system dynamics largely unchanged.

Outcomes Are System-Level Properties

Health outcomes are not produced by individual tools. They emerge from the interaction of coverage continuity, care coordination, clinical decision making, social conditions, and administrative stability over time.

Improving outcomes requires alignment across institutions and accountability across settings. It depends on governance structures that define responsibility for results, not just activity. These conditions are difficult to create in systems organized around episodic intervention and localized incentives.

Innovation can improve specific processes within this environment, but outcomes reflect the system as a whole. When system design remains fragmented, outcome improvement remains constrained regardless of tool quality.

Capital Incentives Favor Activity Over Impact

Investment logic plays a central role in this divergence. Health technology is often evaluated based on growth metrics such as adoption, engagement, utilization, and enterprise penetration.

These signals are measurable and comparable across companies, while health outcomes remain difficult to attribute and standardize.

Outcome improvement unfolds over longer time horizons and across multiple actors. Attribution is diffuse. Measurement is complex. Returns are harder to isolate. As a result, capital flows toward innovation that demonstrates activity rather than sustained improvement in health status.

This dynamic does not imply misaligned intentions. It reflects structural realities of financing innovation inside systems that do not assign clear ownership over outcomes.

Measurement Shapes What Scales

What gets measured governs what scales.

Healthcare measurement infrastructure tracks utilization, cost, and operational throughput far more consistently than longitudinal health outcomes. Clinical improvement is often inferred indirectly or assessed within narrow populations. Data systems prioritize billing, compliance, and reporting requirements over continuity and effectiveness across time.

In this environment, innovation that improves measurable processes is easier to validate and expand than innovation that changes outcomes through coordination, prevention, or sustained engagement.

Outcome improvement requires measurement systems capable of tracking health across settings and life stages. Those systems remain underdeveloped relative to the pace of innovation.

Fragmentation Absorbs Gains

When innovation enters fragmented delivery environments, its benefits are often diluted. Gains achieved in one part of the system may be offset elsewhere.

Improved diagnostics do not guarantee follow-up. Enhanced monitoring does not ensure continuity of care. Efficiency gains in one setting may shift costs to another.

These effects are not failures of technology. They are predictable consequences of systems that lack shared accountability for outcomes.

Innovation can raise the ceiling of what is possible. Fragmentation determines how much of that potential is realized.

Scaling Tools Without Redesigning Systems

Health innovation has succeeded in scaling tools. It has been less successful in scaling systems capable of converting those tools into durable improvements in health.

This imbalance explains why the pace of innovation has outstripped the pace of outcome improvement. It also explains why continued investment alone is unlikely to close the gap.

Until outcomes are treated as shared responsibilities rather than incidental results, innovation will continue to move faster than improvement. The system will remain rich in tools and poor in alignment.

Explore partnership opportunities with an editorial distribution platform reaching 1.8M+ people monthly.