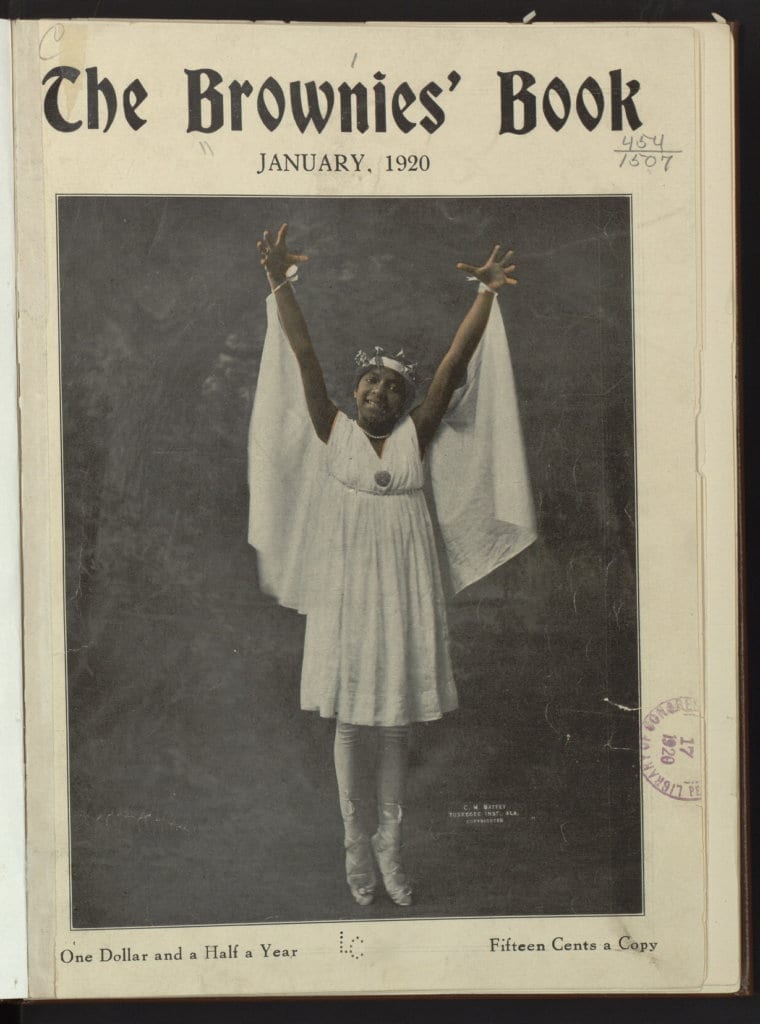

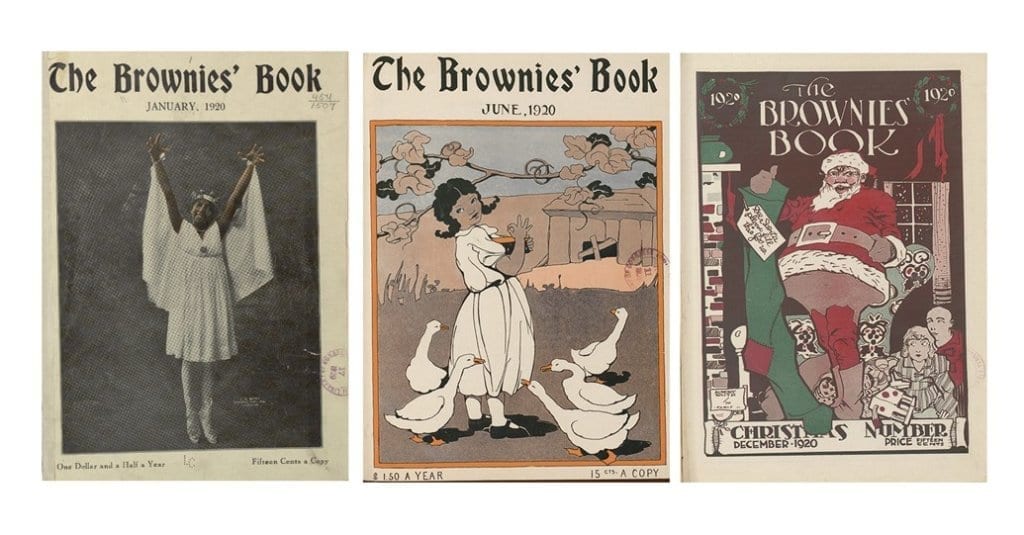

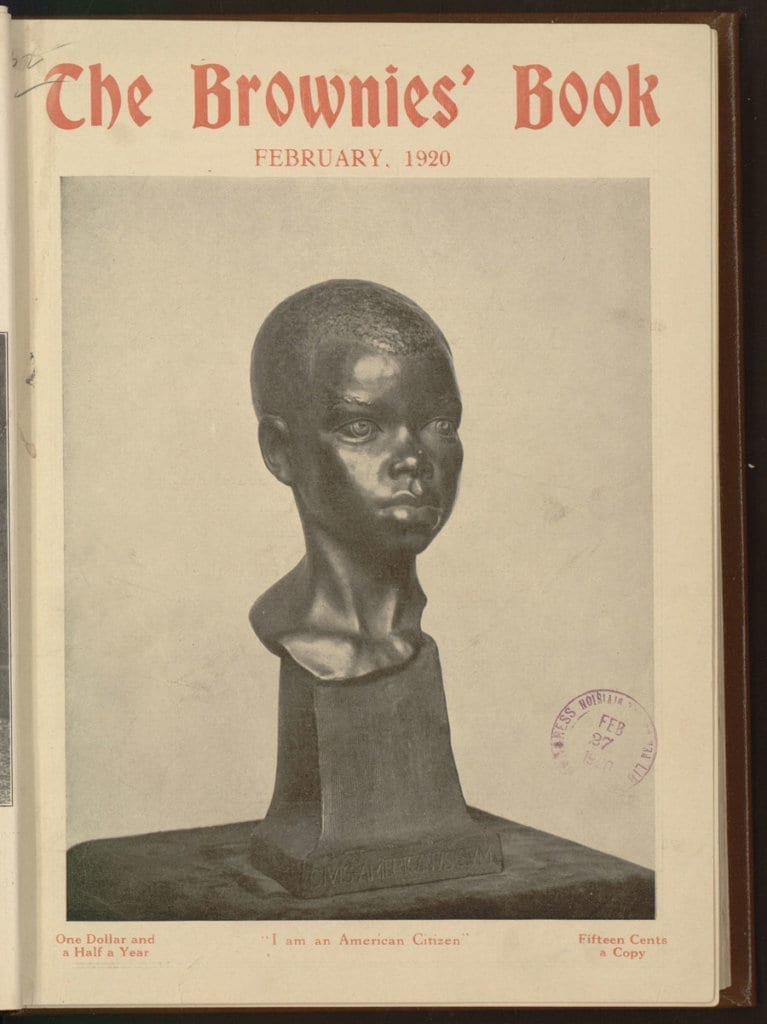

Every revolutionary magazine needs a striking cover, and in January 1920, one appeared. It was a photograph of an African-American girl donning a fairy costume and crown. The title page of that issue contained an even bolder statement: “This is The Brownies’ Book,” it proclaimed in large font, “A Monthly Magazine For the Children of the Sun. Designed for All Children, But Especially For Ours.”

When The Brownies’ Book first hit presses in 1920, stories for or about Black children were largely missing from the landscape of children’s literature. And what did exist, from The Story of Little Black Sambo to poems like Ten Little Niggers that could be found in popular children’s magazines like St. Nicholas, was riddled with grotesque caricatures and stereotypes. As the creators of The Brownies’ Book, including the scholar and visionary W.E.B. Du Bois, put it: “All of the Negro child’s idealism, all his sense of the good, the great and the beautiful is associated with White people … He unconsciously gets the impression that the Negro has little chance to be great, heroic or beautiful.”

The Brownies’ Book, which cost 15 cents per copy, set out to do just that: to give the “Children of the Sun” the chance to see positive, heroic and beautiful impressions of themselves — and to help build up an armor of pride to protect them from the racism they were sure to encounter in their lives. And in doing that, the magazine not only helped alter the perspectives of its young readers but also lay the foundation for a century of Black children’s literature to follow.

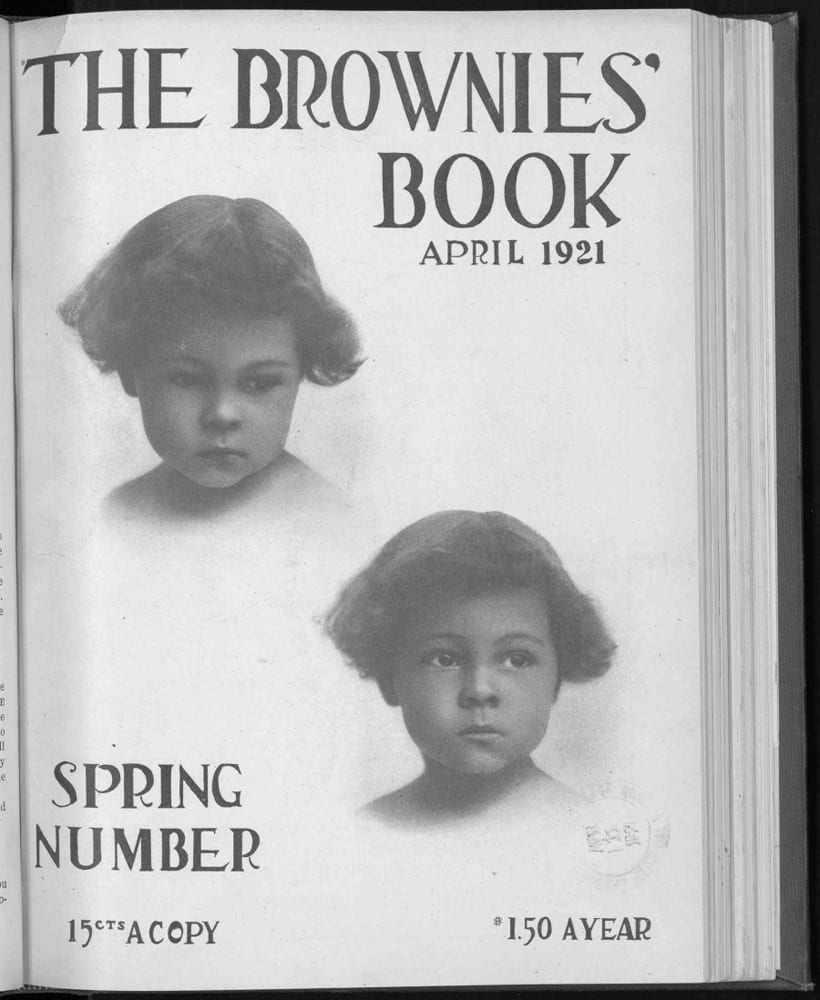

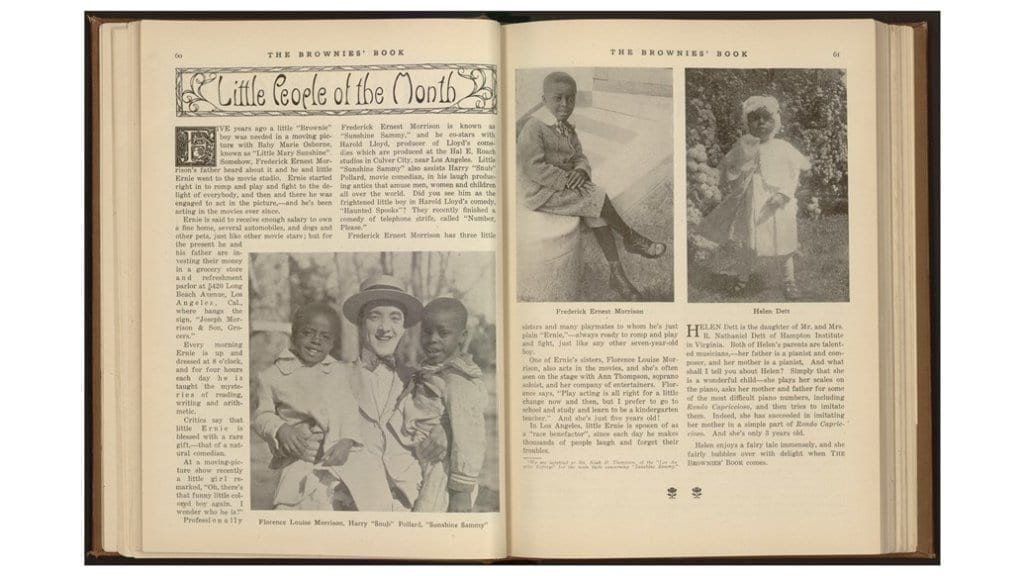

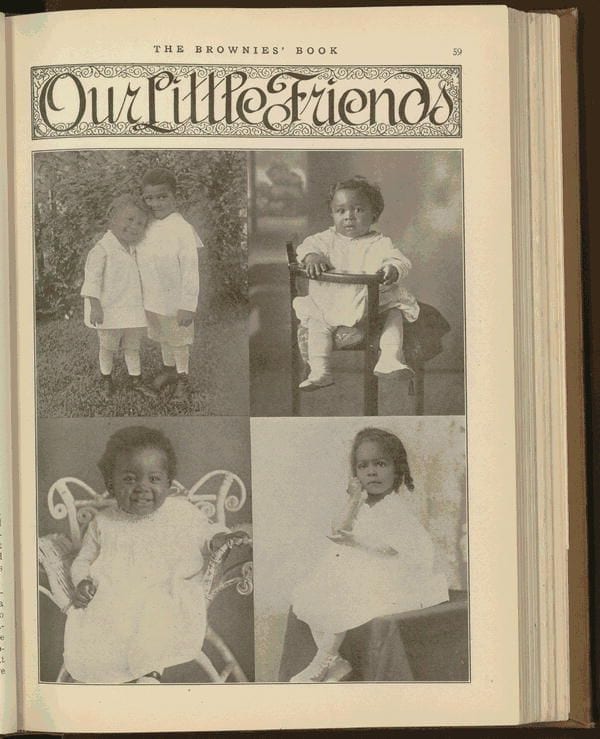

The magazine featured stories, fairy tales, poems, games, songs, African folktales, and illustrated images of all types of Black girls and boys. It featured letters from the young readers themselves and a section entitled “As the Crow Flies,” which reported significant news and events from all over the world. The features were both entertaining and instructive. In “Dolly’s Dream,” for example, a 6-year-old girl wishes to have blonde curls just like her favorite doll, and she is given them by a fairy godmother in a dream, only to realize that nobody recognizes her as a result. When she awakens, she is happy to discover that she still has her black curls.

The Brownies’ Book also provided a forum for showcasing the art of aspiring Black writers and illustrators, including works from a 19-year-old Langston Hughes. Message books that are not also good literature do not work nearly as well, argues Dianne Johnson-Feelings, a professor of African-American literature at the University of South Carolina and editor of The Best of The Brownies’ Book. “It did start focusing people at creating literature aimed primarily at a Black audience,” says Johnson-Feelings, “but it was not only for Black readers. Good literature is for everybody.”

The Brownies’ Book ran from just January 1920 to December 1921 before encountering financial difficulties and ceasing to publish, but it helped foster a much longer lasting sense of pride and self-identity in its young readers and played a key part in sparking the development of African-American children’s literature. Du Bois claimed in his autobiography that The Brownies’ Book was one of the most satisfying efforts of his life.

The magazine was in many ways ahead of its time — and even our own, in which stories for Black children and by Black authors and illustrators continue to be underrepresented in children’s literature. But it was nonetheless an important and impactful effort. “If you wait until you think society is ready, then strides would never be taken,” says Johnson-Feelings. “If you wait for everyone’s hearts to change, then nothing ever changes on a big scale. So big thinkers do their thing and hope that everyone else catches up.”

Source: OZY