Nestled in the heart of Yeadon, Pennsylvania lies a hidden gem of historical significance and cultural heritage: Nile Swim Club (NSC). Far more than just a place to cool off on a hot summer’s day, the Nile Swim Club stands as a testament to resilience, community, and the fight for equality in America.

Established in 1959, Nile Swim Club was born out of necessity during a time of deep racial segregation. African Americans in the region faced limited access to public pools and recreational facilities due to discriminatory policies and practices. Denied entry to white-owned establishments, they were left with few options for leisure and relaxation.

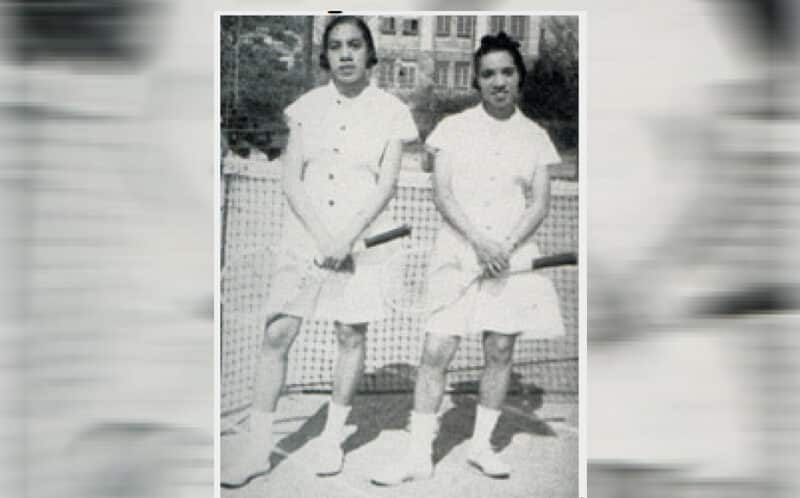

In response to this injustice, a group of African American entrepreneurs and community leaders came together to create a space where their families could gather, swim, and socialize without fear of discrimination or prejudice. Thus, the Nile Swim Club was founded, providing a sanctuary where African American families could escape the oppressive realities of segregation and enjoy the simple pleasures of summertime.

The significance of NSC extends far beyond its role as a recreational facility. It served as a focal point for the local African American community, fostering a sense of belonging and pride in the face of adversity. For many, the club became a second home, a place where lifelong friendships were formed, and cherished memories were made.

Moreover, the Nile Swim Club played a vital role in the broader struggle for civil rights and equality. At a time when racial tensions ran high, the club stood as a beacon of hope and progress, challenging the status quo and paving the way for greater inclusivity and diversity in public spaces.

Throughout the years, the club has weathered its fair share of challenges, including financial difficulties and changing demographics. Yet, despite these obstacles, the club has remained steadfast in its commitment to preserving its rich history and heritage.

Today, Nile Swim Club continues to thrive as a beloved community institution, welcoming visitors of all backgrounds to experience its unique blend of history, culture, and camaraderie. From its sparkling swimming pools to its lush green grounds, the club remains a testament to the enduring power of unity and resilience.