Art is often discussed as expression, creativity, or market activity. At scale, however, art functions differently. It becomes infrastructure.

Once art moves beyond individual production and consumption, it begins to shape institutions, cities, capital flows, and collective memory. Decisions about what is collected, exhibited, preserved, and funded influence not only taste, but legitimacy and power over time.

Institutional custody does not guarantee permanence. It grants authority over duration, movement, and reallocation, which is itself a form of power.

Understanding art as infrastructure changes how it is evaluated and governed.

Art as a Signaling System

At the institutional level, art operates as a signaling mechanism.

Museums, foundations, universities, and civic spaces use art to communicate values, credibility, and alignment. Collections signal seriousness. Curatorial decisions signal worldview. Patronage signals belonging. These signals travel across audiences that include donors, governments, investors, and the public.

This signaling function explains why art persists as a strategic concern even during periods of economic contraction. While transaction volumes fluctuate, institutions continue to invest in collections and cultural assets because the reputational and symbolic value compounds over time.

Global art market sales totaled approximately $57.5 billion in 2024, reflecting a contraction from peak levels but continued transactional depth and participation across segments. This activity underscores that art markets adjust, but the underlying institutional role of art remains durable.

Beyond Transactions, Toward Stewardship

Markets treat art as a series of transactions. Institutions treat art as a long-term responsibility.

Once art enters institutional custody, the primary questions shift. The focus moves away from price discovery and toward stewardship, preservation, and context. Decisions are evaluated based on decades, not cycles.

This distinction matters because it shapes who holds influence. Those who control acquisition budgets, curatorial agendas, and placement decisions ultimately shape which narratives endure and which fade. Visibility follows placement. Legacy follows custody.

Collectors and institutions increasingly articulate this orientation explicitly. Surveys indicate that a large majority of collectors remain optimistic about art’s future, with many prioritizing legacy and cultural contribution over short-term returns. This reflects a broader understanding of art as a store of cultural capital rather than a purely financial asset.

Infrastructure Requires Capital and Governance

Treating art as infrastructure exposes its dependence on capital and governance.

Museums, cultural districts, and public collections require sustained funding, physical space, regulatory alignment, and institutional leadership. Recent investments, such as major museum expansions funded by public and private capital, demonstrate that art infrastructure competes for resources alongside transportation, education, and civic development.

These investments are rarely neutral. They shape urban development, tourism patterns, and cultural authority. Art placed within institutional settings gains permanence and legitimacy that far exceeds the impact of market visibility alone.

As a result, art increasingly intersects with real estate development, public-private partnerships, and philanthropic strategy. Decisions about where art lives determine how it is accessed and how it is remembered.

Control of Art Is Control of Narrative

Because art functions as infrastructure, control matters.

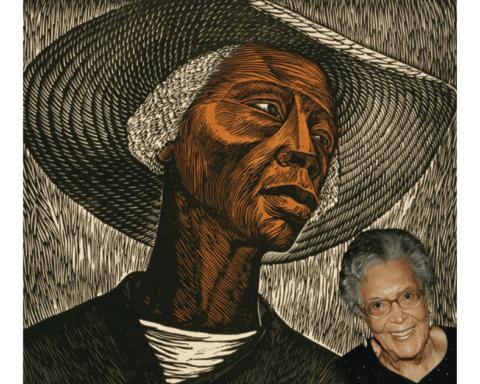

Ownership, placement, and governance determine which stories are preserved and amplified. This is particularly consequential for communities whose cultural production has historically been excluded from institutional custody.

In recent years, Black contemporary art has received increased attention from collectors and institutions, including dedicated sales, acquisitions, and exhibitions. While this shift has expanded visibility, it has also raised questions about control. Who owns the work. Where it resides. Who contextualizes it. And who benefits from its institutionalization over time.

These questions extend beyond representation. They speak to whether cultural capital translates into long-term influence or remains extractive in nature.

Art, Cities, and Long-Term Power

At the city level, art infrastructure shapes identity and economic development.

Cultural institutions anchor districts, attract tourism, and signal global relevance. Cities invest in museums and public art not simply to beautify space, but to establish cultural legitimacy and attract long-term capital.

In this context, art operates alongside transportation systems, universities, and civic institutions as part of a broader infrastructure stack. Its impact is diffuse but persistent, influencing how places are perceived and how resources flow.

This role becomes especially visible in global cities, where cultural capital functions as a competitive advantage.

A Structural View of Art

Viewing art as infrastructure clarifies its real function.

Art shapes systems of meaning that outlast markets. It provides continuity across generations. It reinforces or challenges institutional narratives. It accumulates power quietly through custody, context, and governance.

This perspective does not diminish artistic expression. It situates it within a larger system where decisions about ownership and placement carry consequences beyond aesthetics.

For institutions, collectors, and cultural stewards, this framing shifts the question from what art is worth to what art does.