It’s campaign season in the US, and a charismatic dark horse is running with the slogan ‘make America great again’. According to his opponent, he’s a demagogue; a rabble-rouser; a hypocrite. When his supporters form mobs and burn people to death, he condemns their violence “in such mild language that his people are free to hear what they want to hear”.

He accuses, without grounds, whole groups of people of being rapists and drug dealers. How much of this rhetoric he actually believes and how much he spouts “just because he knows the value of dividing in order to conquer and to rule” is at once debatable, and increasingly beside the point, as he strives to return the country to a “simpler” bygone era that never actually existed.

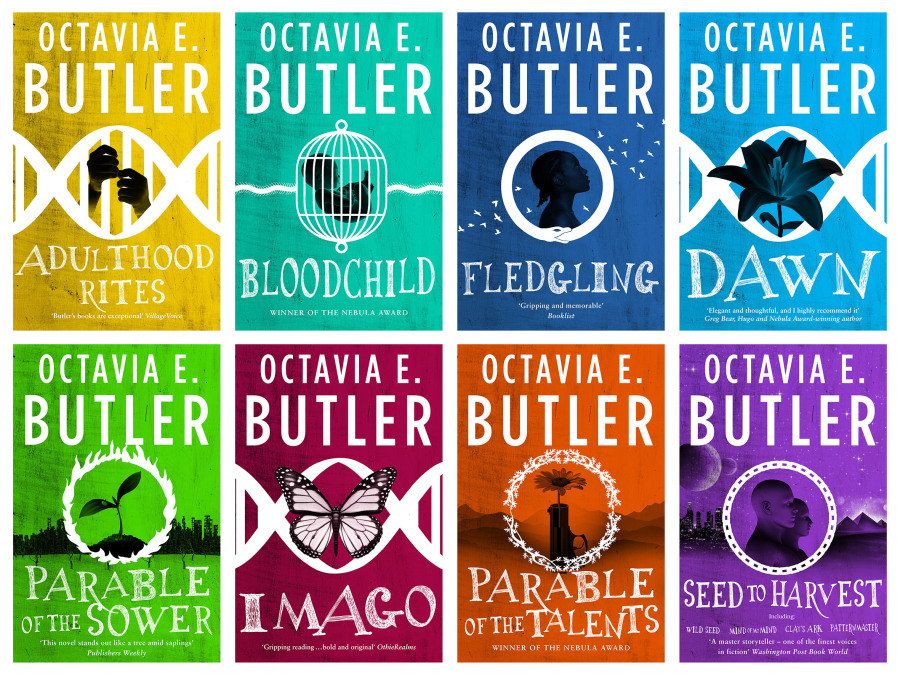

You might think he sounds familiar – but the character in question is Texas Senator Andrew Steele Jarret, the fictional presidential candidate who storms to victory in a dystopian science-fiction novel titled Parable of the Talents. Written by Octavia E Butler, it was published in 1998, two decades before the inauguration of the 45th President of the United States.

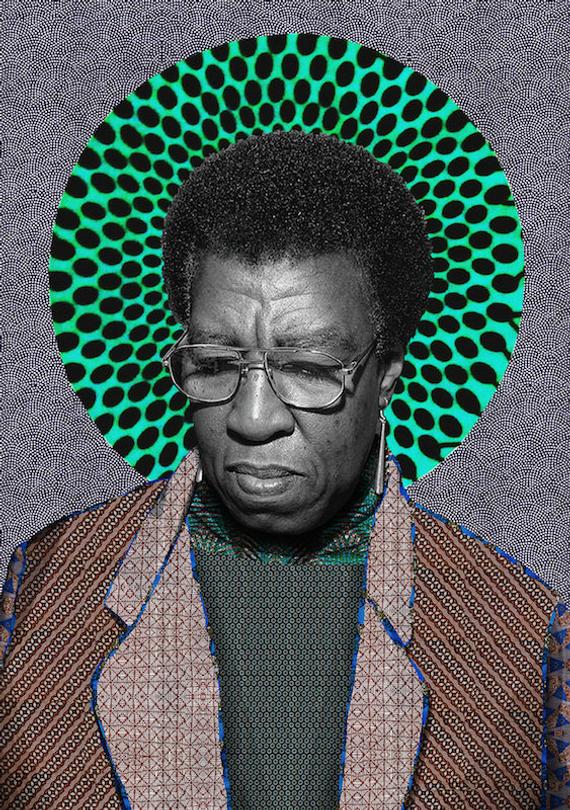

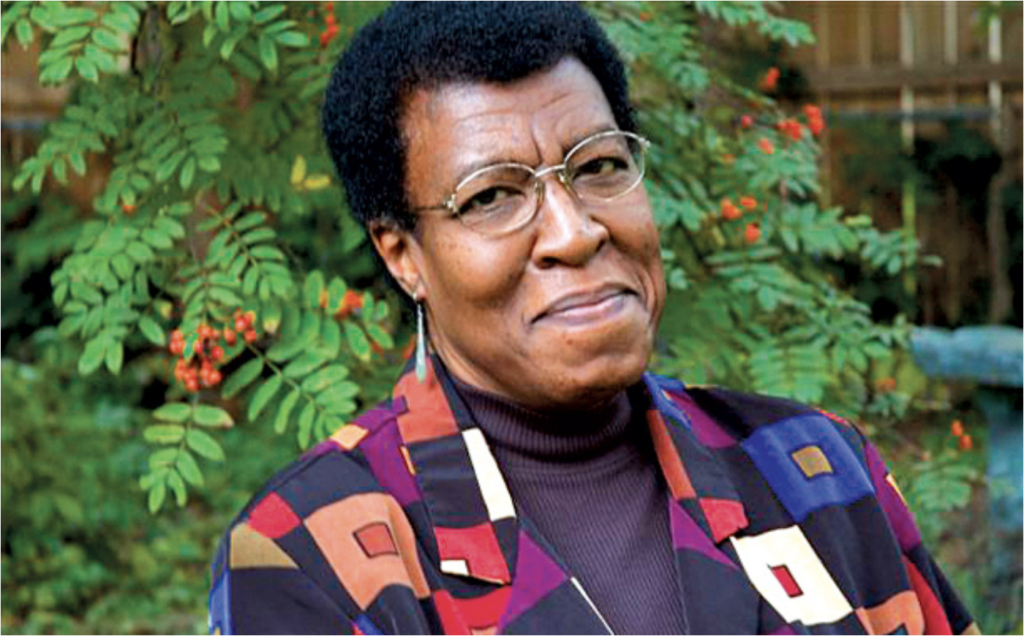

Fourteen years after her early death, Butler’s reputation is soaring. Her predictions about the direction that US politics would take, and the slogan that would help speed it there, are certainly uncanny. But that wasn’t all she foresaw. She challenged traditional gender identity, telling a story about a pregnant man in Bloodchild and envisaging shape-shifting, sex-changing characters in Wild Seed. Her interest in hybridity and the adaptation of the human race, which she explored in her Xenogenesis trilogy, anticipated non-fiction works by the likes of Yuval Noah Harari. Concerns about topics including climate change and the pharmaceutical industry resonate even more powerfully now than when she wove them into her work.

And of course, by virtue of her gender and ethnicity, she was striving to smash genre assumptions about writers – and readers – so ingrained that in 1987, her publisher still insisted on putting two white women on the jacket of her novel Dawn, whose main character is black. She also helped reshape fantasy and sci-fi, bringing to them naturalism as well as characters like herself. And when she won the prestigious MacArthur ‘genius’ grant in 1995, it was a first for any science-fiction writer.

Octavia Estelle Butler was born on 22 June 1947. Her father, a shoeshiner, died when she was very young, and she was raised by her mother, a maid, in Pasadena, California. As an only child, Butler began entertaining herself by telling stories when she was just four. Later, tall for her age and painfully shy, growing up in an era of segregation and conformity, that same storytelling urge became an escape route. She read, too, hungrily and in spite of her dyslexia. Her mother – who herself had been allowed only a scant few years of schooling – took her to get a library card, and would bring back cast-off books from the homes she cleaned.

An alternate future

Through fiction, Butler learnt to imagine an alternate future to the drab-seeming life that was envisioned for her: wife, mother, secretary. “I fantasised living impossible, but interesting lives – magical lives in which I could fly like Superman, communicate with animals, control people’s minds”, she wrote in 1999. She was 12 when she discovered science fiction, the genre that would draw her most powerfully as a writer. “It appealed to me more, even, than fantasy because it required more thought, more research into things that fascinated me,” she explained. Even as a young girl, those sources of fascination ranged from botany and palaeontology to astronomy. She wasn’t a particularly good student, she said, but she was “an avid one”.

After high school, Butler went on to graduate from Pasadena City College with an Associates of Arts degree in 1968. Throughout the 1970s, she honed her craft as a writer, finding, through a class with the Screen Writers’ Guild Open Door Program, a mentor in sci-fi veteran Harlan Ellison, and then selling her first story while attending the Clarion Science Fiction Writer’s Workshop. Supporting herself variously as a dishwasher, telemarketer and inspector at a crisp factory, she would wake at 2am to write. After five years of rejection slips, she sold her first novel, Patternmaster, in 1975, and when it was published the following year, critics praised its well-built plot and refreshingly progressive heroine. It imagines a distant future in which humanity has evolved into three distinct genetic groups, the dominant one telepathic, and introduces themes of hierarchy and community that would come to define her work. It also spawned a series, with two more books, Mind of My Mind and Survivor, following before the decade’s end.

With the $1,750 advance that Survivor earnt her, Butler took a trip east to Maryland, the setting for a novel she wanted to write about a young black woman who travels back in time to the Deep South of 19th-Century America. Having lived her entire life on the West Coast, she travelled by cross-country bus, and it was during a three-hour wait at a bus station that she wrote the first and last chapters of what would become Kindred. It was published in 1979 and remains her best-known book.

The 1980s would bring a string of awards, including two Hugos, the science-fiction awards first established in 1953. They also saw the publication of her Xenogenesis trilogy, which was spurred by talk of ‘winnable nuclear war’ during the arms race, and probes the idea that humanity’s hierarchical nature is a fatal flaw.The books also respond to debates about human genetic engineering and captive breeding programs for endangered species.

Read the rest at BBC Culture