In the heart of Accra, Ghana’s capital, just a few meters from the United States embassy, lie the tombs of W. E. B. Du Bois, a great African-American civil rights leader, and his wife, Shirley.

The founder of the US-based National Association for the Advancement of Colored People moved to Accra in 1961, settling in the city’s serene residential area of Labone and living there until his death in August 1963.

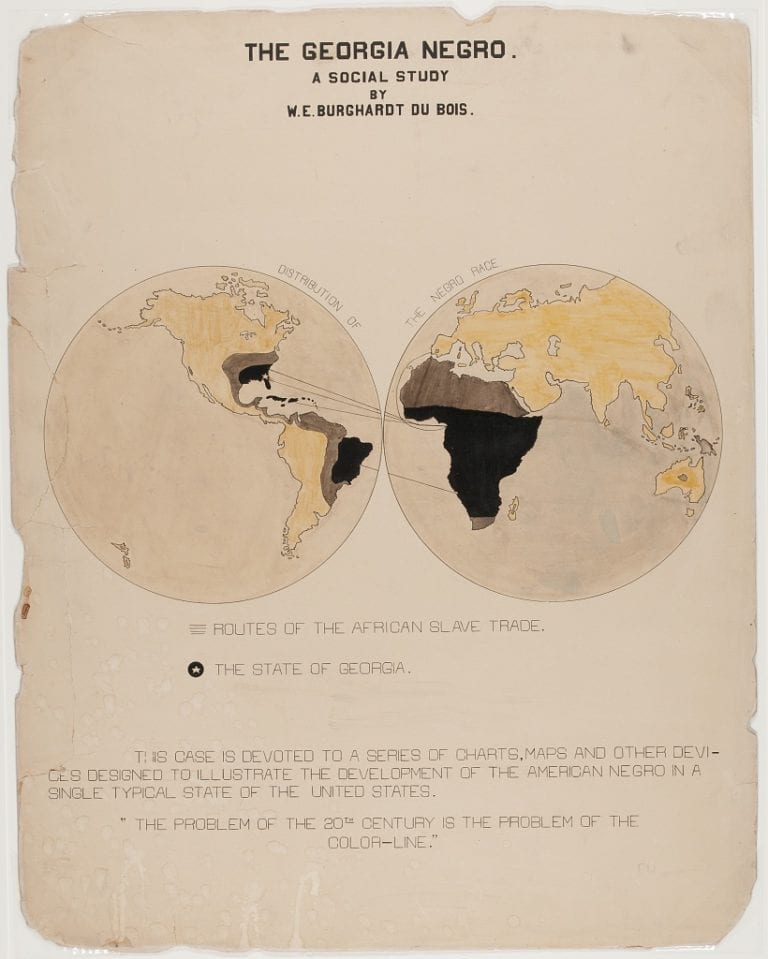

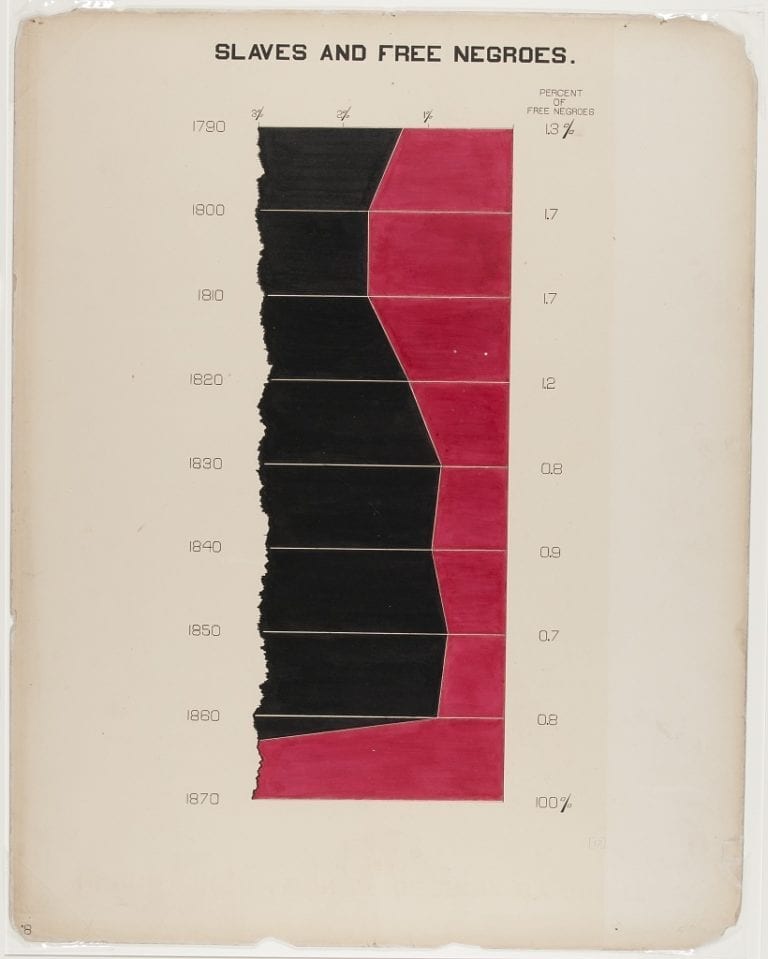

Du Bois’s journey to Ghana may have signaled the emergence of a profound desire among Africans in the diaspora to retrace their roots and return to the continent. Ghana was a major hub for the transatlantic slave trade from the 16th to the 19th centuries.

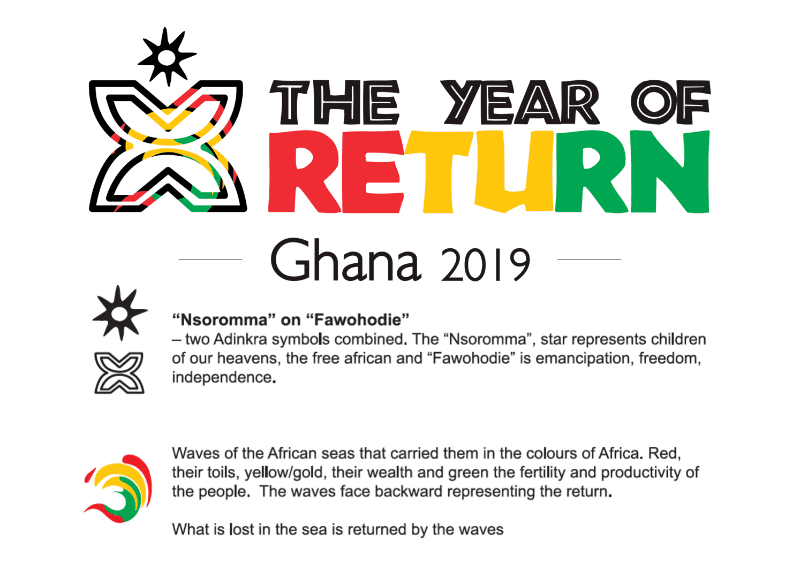

In Washington, D.C., in September 2018, Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo declared and formally launched the “Year of Return, Ghana 2019” for Africans in the Diaspora, giving fresh impetus to the quest to unite Africans on the continent with their brothers and sisters in the diaspora.

At that event, President Akufo-Addo said, “We know of the extraordinary achievements and contributions they [Africans in the diaspora] made to the lives of the Americans, and it is important that this symbolic year—400 years later—we commemorate their existence and their sacrifices.”

200 years since the abolition of slavery

US Congress members Gwen Moore of Wisconsin and Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas, diplomats and leading figures from the African-American community, attended the event.

Representative Jackson Lee linked the Ghanaian government’s initiative with the passage in Congress in 2017 of the 400 Years of African-American History Commission Act.

Provisions in the act include the setting up of a history commission to carry out and provide funding for activities marking the 400th anniversary of the “arrival of Africans in the English colonies at Point Comfort, Virginia, in 1619.”

Since independence in 1957, successive Ghanaian leaders have initiated policies to attract Africans abroad back to Ghana.

In his maiden independence address, then–Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah sought to frame Africa’s liberation around the concept of Africans all over the world coming back to Africa.

“Nkrumah saw the American Negro as the vanguard of the African people,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr., Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard, who first traveled to Ghana when he was 20 and fresh out of Harvard, afire with Nkrumah’s spirit.

“He wanted to be able to utilize the services and skills of African-Americans as Ghana made the transition from colonialism to independence.”

Ghana’s parliament passed a Citizenship Act in 2000 to make provision for dual citizenship, meaning that people of Ghanaian origin who have acquired citizenships abroad can take up Ghanaian citizenship if they so desire.

That same year the country enacted the Immigration Act, which provides for a “Right of Abode” for any “Person of African descent in the Diaspora” to travel to and from the country “without hindrance.”

The Joseph Project

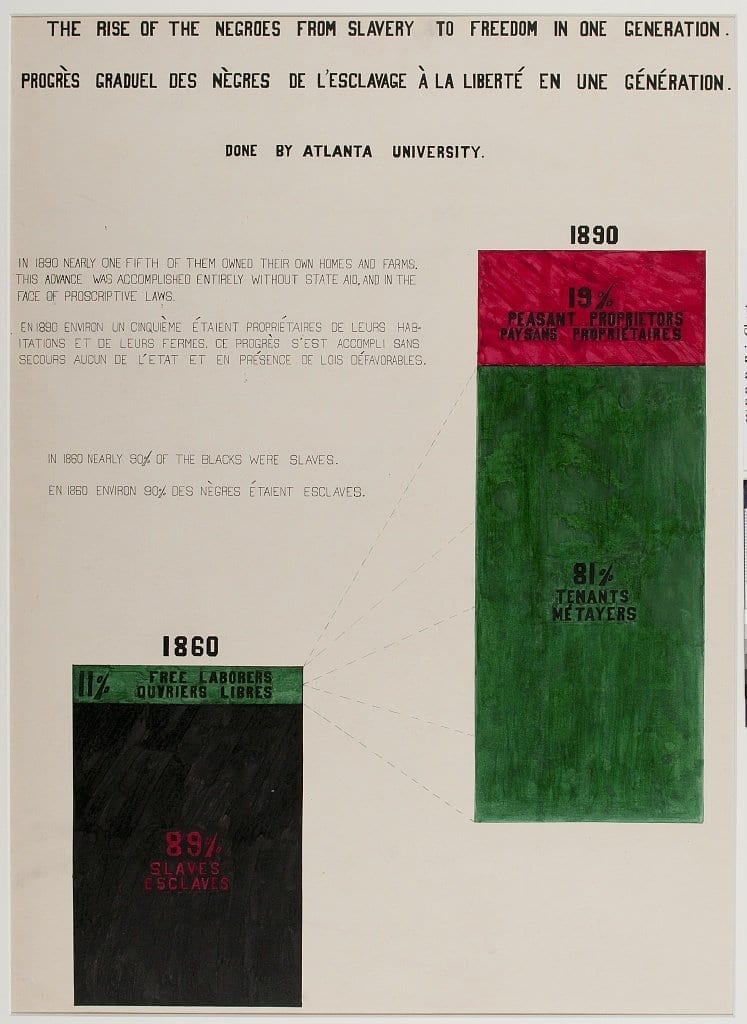

In 2007, in its 50th year of independence, the government initiated the Joseph Project to commemorate 200 years since the abolition of slavery and to encourage Africans abroad to return.

Similar to Israel’s policy of reaching out to Jews across Europe and beyond following the Holocaust, the Joseph Project is named for the Biblical Joseph who was sold into slavery in Egypt but would later reunite with his family and rule Egypt.

The African-American community is excited about President Akufo-Addo’s latest initiative. In social media posts, many expressed interest in visiting Africa for the first time.

Among them is Amber Walker, a media practitioner who says that 2019 is the time to visit her ancestral home.

“The paradox of being an African-American is that we occupy spaces where we are not being considered as citizens. So I love the idea of Ghana taking the lead to kind of help African-Americans claim their ancestral space,” she told Africa Renewal. “It is a step in the right direction.

“It is definitely comforting because that kind of red carpet has not been rolled out by our oppressors in the Western world,” she added.

In making the announcement, President Akufo-Addo said: “Together on both sides of the Atlantic, we’ll work to make sure that never again will we allow a handful of people with superior technology to walk into Africa, seize their people and sell them into slavery. That must be our resolution, that never again, never again!”

But Walker took issue with Akufo-Addo for appearing to downplay the actions of some Africans in the slave trade.

“In the president’s [Akufo-Addo’s] statement, he sounds like the entire blame is placed on white people coming in with weapons and taking black people away, but that’s not necessarily the history. So I think that needs to be acknowledged,” she said.

She suggested a form of reconciliation such as took place in post-apartheid South Africa—a truth and reconciliation process that will satisfy the millions of Africans whose forefathers were sold into slavery.

In 2013 the United Nations declared 2015–2024 the International Decade for People of African Descent to “promote respect, protection and fulfilment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms of people of African descent.”

The theme for the ten-year celebration is “People of African descent: recognition, justice and development.”

The “Year of Return, Ghana 2019” will coincide with the biennial Pan African Historical Theatre Festival (Panafest), which is held in Cape Coast, home of Cape Coast Castle and neighbouring Elmina Castle—two notable edifices recognized by UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) as World Heritage Sites of the slave era.

Source: IPS News