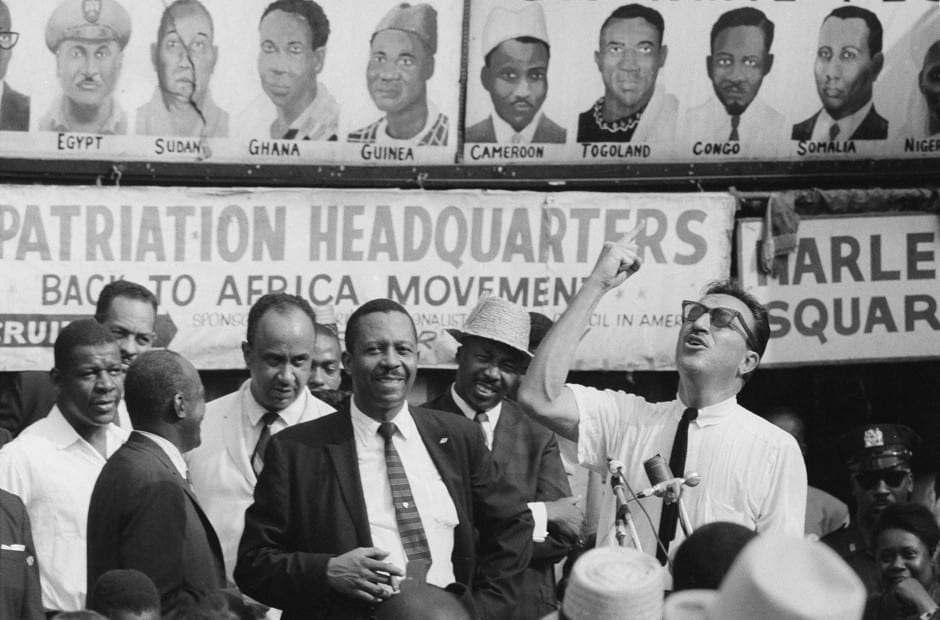

In the spring of 1968, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover announced to his agents that COINTELPRO, the counter-intelligence program established in 1956 to combat communists, should focus on preventing the rise of a “Black ‘messiah’” who sought to “unify and electrify the militant black nationalist movement.”

The program, Hoover insisted, should target figures as ideologically diverse as the Black Power activist Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture), Martin Luther King Jr., and Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad.

Just a few months later, in October 1968, Hoover penned another memo warning of the urgent menace of a growing Black Power movement, but this time the director focused on the unlikeliest of public enemies: black independent booksellers.

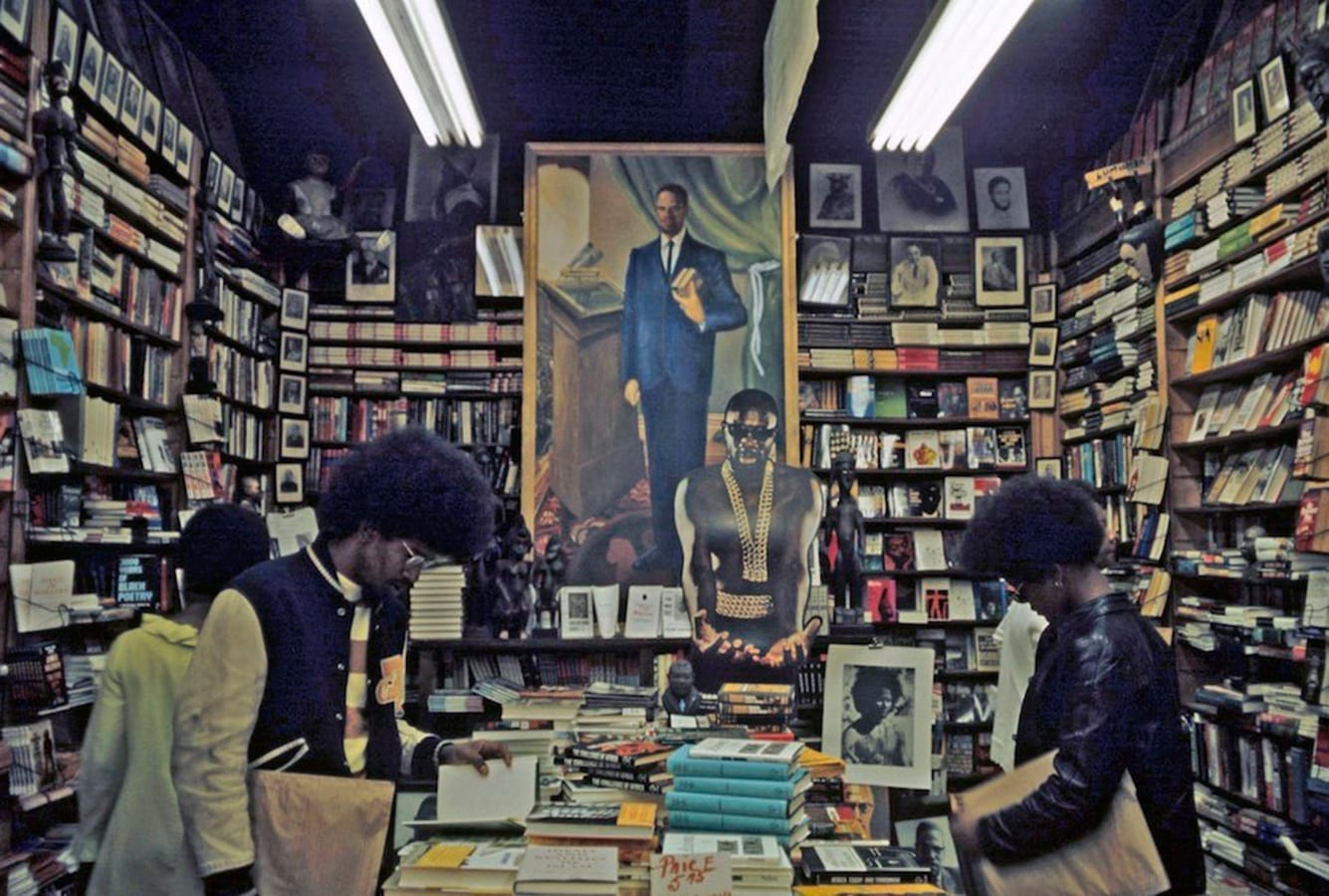

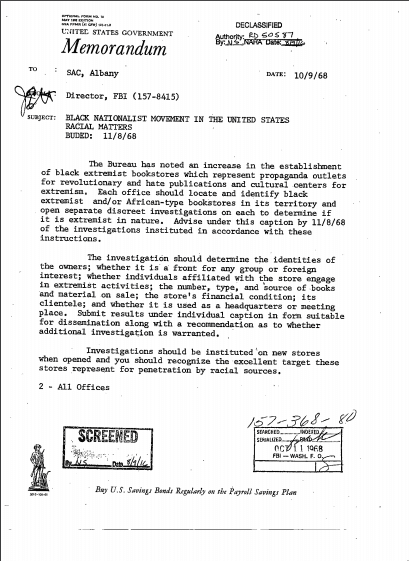

In a one-page directive, Hoover noted with alarm a recent “increase in the establishment of black extremist bookstores which represent propaganda outlets for revolutionary and hate publications and culture centers for extremism.”

The director ordered each Bureau office to “locate and identify black extremist and/or African-type bookstores in its territory and open separate discreet investigations on each to determine if it is extremist in nature.”

Each investigation was to “determine the identities of the owners; whether it is a front for any group or foreign interest; whether individuals affiliated with the store engage in extremist activities; the number, type, and source of books and material on sale; the store’s financial condition; its clientele; and whether it is used as a headquarters or meeting place.”

Perhaps most disturbing, Hoover wanted the Bureau to convince African American citizens (presumably with pay or through extortion) to spy on these stores by posing as sympathetic customers or activists.

“Investigations should be instituted on new stores when opened and you should recognize the excellent target these stores represent for penetration by racial sources,” he ordered.

Hoover, in short, expected agents to adopt the ruthless tactics of espionage and falsification they deployed against civil-rights and Black Power activists, and now use them against black-owned bookstores.

Hoover’s memo offers us a troubling glimpse of a forgotten dimension of COINTELPRO, one that has escaped notice for decades: the FBI’s war on black-owned bookstores.

At the height of the Black Power movement, the FBI conducted investigations of such black booksellers as Lewis Michaux and Una Mulzac in New York City, Paul Coates in Baltimore (the father of The Atlantic national correspondent Ta-Nehisi Coates), Dawud Hakim and Bill Crawford in Philadelphia, Alfred and Bernice Ligon in Los Angeles, and the owners of the Sundiata bookstore in Denver.

And this list is almost certainly far from complete because most FBI documents pertaining to currently living booksellers aren’t available to researchers through the federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

The FBI appears to have wound down its surveillance of black bookstores by the middle of the 1970s, in the wake of Hoover’s death and the formal conclusion of COINTELPRO. As the Black Power movement declined in the late 1970s, so did black bookstores, and their numbers significantly dwindled by the start of the ‘80s (before experiencing a resurgence in the early 1990s). Looking back, it’s worth asking if the Bureau’s investigations may have undermined the viability of these black-owned businesses, creating undue stress for owners already struggling to make ends meet and scaring away customers who wanted to avoid any encounters with law-enforcement officials.

Read more at The Atlantic